Get to know Dr. Zur

Click a feature below to learn more about the life and career of Dr. Ofer Zur.

Forensic-Consulting

Ofer Zur, Ph.D. is an experienced forensic consultant in mental health related issues. As noted in his Curriculum Vitae, he has been teaching Ethics at the graduate and post-graduate levels for over 25 years, and he has published extensively in the area of standard of care as it pertain to issues such as confidentiality, record keeping, scope of practice, diagnosis, treatment and the broad area of therapeutic boundaries. He has been consulting with psychologists, social workers, marriage and family therapists, counselors and attorneys on issues of boundaries and the standard of care regarding licensing board complaints, personal injury and medical malpractice cases.

Find out more about Forensic-Consulting

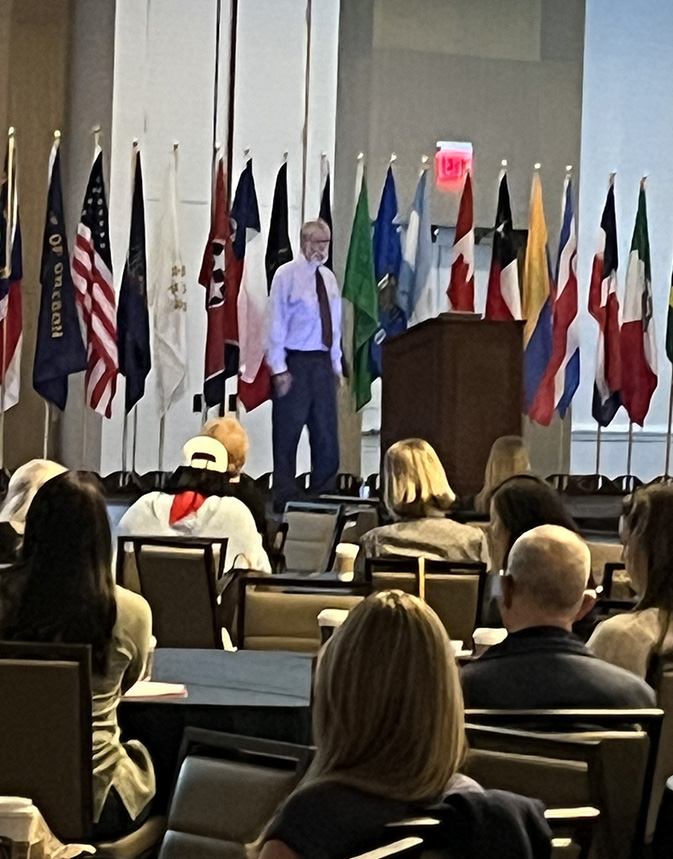

Teaching

Invite Dr. Zur to present a lecture, workshop or keynote address for your organization. Find out more about Seminars, Keynotes, Workshops, Lectures, Live Presentations, Webinars, Teleconferences & Radio Interviews.

Find out more about Teaching and Speaking

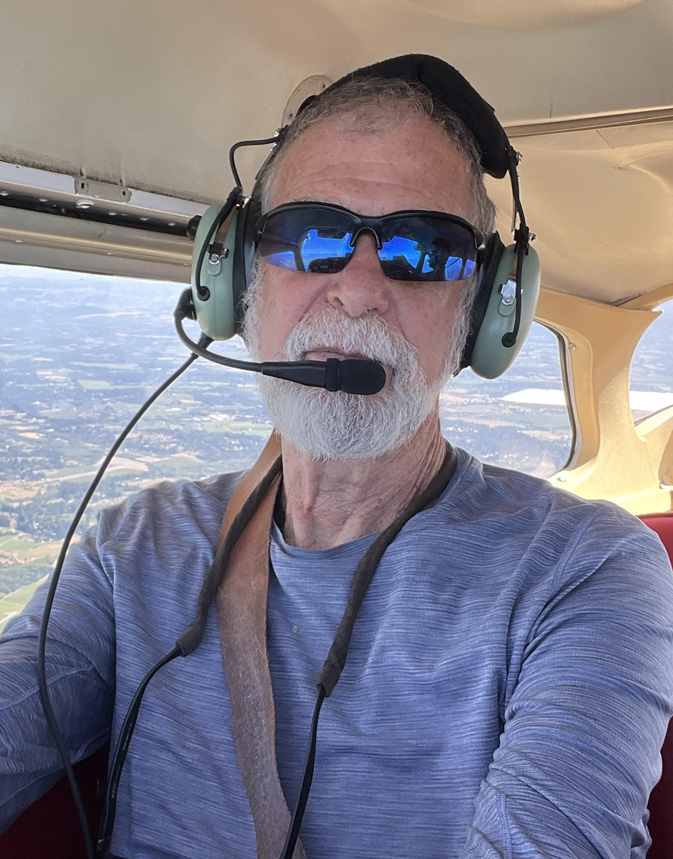

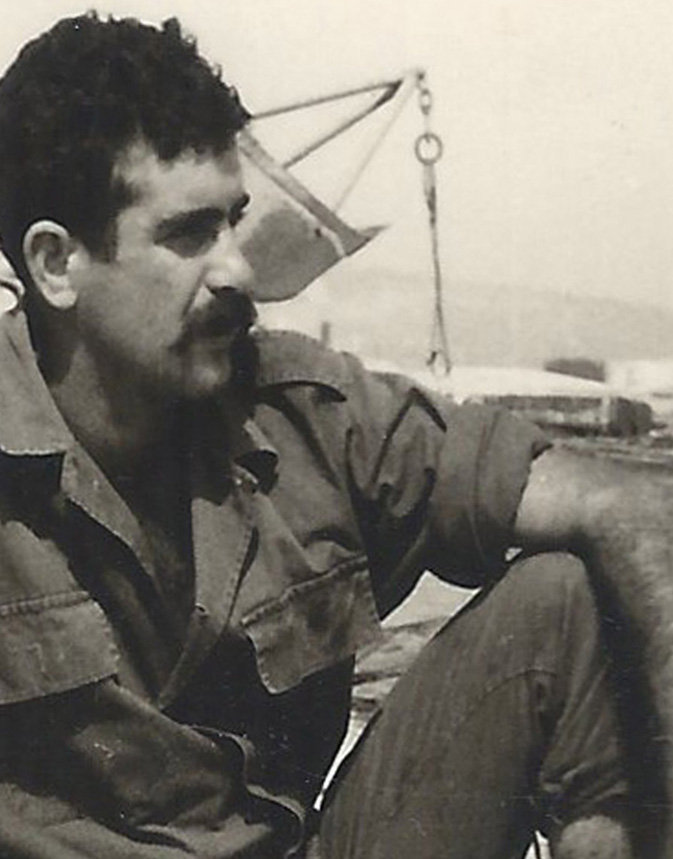

About Dr. Ofer Zur

Online Courses

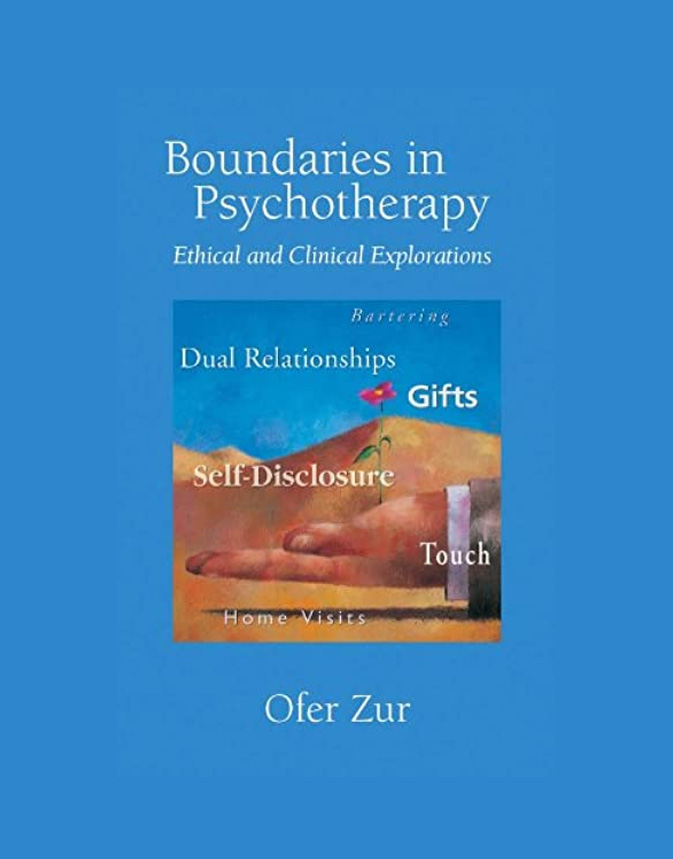

Books by Dr. Zur

Articles by Dr. Zur

Most Popular Articles, Videos & Audios By Dr. Zur

I have written hundreds of articles and produced numerous video and audio recordings on a variety of topics throughout my career available in my complete archive. This page features the topics that are most endeared to my heart and compose a significant part of my legacy.

Boundaries & Dual Relationships in Psychotherapy and Counseling

Dying Well Can Help You Live Well - Facing Death ‘Head-On’

The Blessing in Trauma – On Post-Traumatic Growth

See complete archive of all Dr. Ofer Zur articles, clinical updates, audio recordings and videos.