Peace & Justice in Mother’s Milk

I was born in Israel in 1950 to pioneer parents. My mother, a German Jew, was an intellectually rigorous psychologist. My father, an Hungarian Jew, was gentle and poetic but also a labor organizer and engineer.Both had lost most of their families in the Holocaust. Together, they were a visionary, optimistic, determined, and idealistic pair who mirrored the exciting tenor of the times in Israel as the new nation was born from the ashes of the Holocaust. It was only natural that concerns with justice, peace, integrity, compassion, and fairness were discussed daily around our dinner table with lively discussions about social justice, peaceful co-existence with neighboring Arab countries, and the rights of women, Jewish immigrants from Arab countries, and Israeli Arabs.

Born in Israel

To inspiring, loving parents

My destiny molded in their values of justice, compassion & peace

Like a ship beginning a voyage of self-discovery

My parents, the anchors of good deeds & righteousness

my port of calling,

my dock of endless, enduring love.

Questioning Authority: The Early Years

The years passed and I grew to be a young man. I had a very close group of friends in the youth movement (Hashomer Hatzair) and was close to my older sister. I loved sports, hiking, backpacking, swimming, and basketball, but was also a keen reader of many subjects. In the course of absorbing so much new information and so many new ideas, I soon found I had a passion for critical thinking and its natural consequence: a desire to improve the society I lived in and to question existing ‘truths’ and unquestioned/given assumptions. Alongside my family and friends, I was politically active in promoting peaceful co-existence between Israelis and Palestinians and in opposing religious oppression and manipulation by the extremist religious Jews….and it all began at our dinner table where Martin Buber, Rollo May, and other existentialists were part of the menu.

A thirst for knowledge blossomed in me

Like a bud growing in springtime,

poking through the newly thawed soil

An examination of life, a proclivity

to challenge rigid dogmas and assumptions

Like an ember that slowly simmered

My quest to question the unquestioned began

Encounter with Phosphorous Grenade at Age 10

At age 10, during a Purim holiday celebration (similar to Mardi Gras) where thousands of Israelis gathered in the center of Tel-Aviv to celebrate, an Israeli soldier mistakenly launched a phosphorous grenade into the crowd while intending to throw a colorful and harmless smoke grenade. The burning phosphorous struck both my legs and my hair, turning me into living torch. Due to the nature of phosphorous, which sticks to the skin and can burn without oxygen, it was hard to put the fire out and I ended up with third degree burns on my legs and a scar on my hairline and spent a month in the hospital. (For the rest of my life I could always resonate with the famous Vietnamese Napalm-Girl, who was photographed in 1972 screaming in torturous pain, after U.S. air-force reprehensibly, inhumanly and immorally dropped napalm on her village.) Oddly enough, my most vivid memories of this ordeal were having fun in the hospital riding a wheelchair on two wheels and spending time with my mother who had also received burns from the same grenade and was in the next hospital room.

I had been set on fire

A young child burned by a phosphorus grenade

The mood, a juxtaposition of celebration and terror

My heart choked by fear

Burns covered my body

Purple scars covered my skin

remnants of a painful memory

I became stronger from this surreal experience

more resilient and less fearful

Justifying One’s Existence by Doing Good (Daily)

Family times were precious and certainly have had a lifelong effect on both my sister (four years older) and me. I am an amalgam (powwow) of my parents: my mother’s rigorous intellect and my father’s gentle soul and both their devotion to social justice and to ‘doing good’. My name also reflects these complementary polarities within me. “Ofer” means fawn in Hebrew, a creature that is gentle and tender, while “Zur” (or “Tsur” or “Tsoor” in Hebrew) means hard rock and represents firmness and rigorousness. At dinner time we often would be asked about any good deeds we had done that day or about any worries or feelings. As a result, for many years, I felt I had to ‘justify my existence’ by doing a daily good deed. I remember one example of a family discussion just after my bicycle had been stolen. Obviously, I was furious, but my parents reminded me of how privileged (not wealthy) we were and that the boy who stole my bicycle probably has come from a poor or deprived home.

To do good

Values woven into the fiber of my being

A virtuous existence

Peering outside of myself

To step into the shoes of another

To hold a hand

Touch a heart

Mold a life

Stepping into the Void - On Being a Paratrooper

The Israeli army is a rite of passage for almost all young Israelis and during my service I faced barriers and boundaries that I had never before encountered. I was a paratrooper and I will forever remember the first time I stood at the launch door of an airplane, thousands of feet above the earth - poised at a fundamental boundary between the real and the ethereal - and stepped forward into the void. It was a transforming experience, fraught with suspense and fear but also imbued with joy and the instant dawning of a new perspective. Floating, falling, what a metaphor for Life! - but also entrusting my life to a slip of silk, certain that the canopy would open, trusting to the unknown.

A door separated me from

airplane and sky

One foot placed gingerly on a metal floor,

And the other foot on a cloud

Holding on, letting go

Sailing through whisps of white

Cottonball clouds

Floating endlessly above the earth

Gliding gently below.

Looking at Death Straight in the Eyes: An Encounter w/ Death

Soon after, as a lieutenant and combat officer, just 19 years old, viewing life as a prism of possibilities, I found myself at the greatest boundary of all, that of life and death. For the first time, I held a soldier’s dead body in my arms. Simplicity and innocence vanished and once again a new perspective opened before me, a new consciousness. I felt so profoundly the preciousness, the fragility of life and the importance of living each day fully, with care and integrity, as if it were my last day on earth. To this day, I try to live that way.

Life with its infinite possibilities

Could vanish without warning

Cradling a soldier’s dead body in my arms

Mourning a life taken too soon

A new perspective formed in my consciousness

An appreciation for each day

As it could be my last

Shooting the Light Bulb – How Dumb is That?

While some boundaries are physical, existential, or spiritual, others are developmental, metaphorical, or metaphysical. I remember a time, during my military service, when three of us, all officers, were housed in a cement bunker. Late one night, we were all very tired and had turned in for a good night’s sleep. I was already in bed and, instead of doing the obvious of getting up and turning off the light switch, I reached for my handgun and shot out the single light bulb hanging from the ceiling. While I accurately hit the bulb, which effectively turned the light off, the bullet ricocheted wildly around the cement walls for what seemed like a very long time, seriously endangered the life of all three of us. On my list of boundaries, this would easily rank as a highly reckless, stupid, and an utterly irresponsible way of pushing boundaries - and fate.

The bullet ricocheted throughout the room,

after initially piercing the air,

and making the room change from light to dark

In the moment, the only murmur was my heart

Which grew louder, telltale heart, like from Poe,

I had risked their, our… lives

True Freedom: Riding Motorcycles & Jeeps in the Desert

One of my many assignments in the army was patrolling the Arava and the Negev desert from the Dead Sea in the north to the resort town of Eilat in the south, situated at the northern tip of the Red Sea. I loved the desert; I always did. There is something in its vastness, dryness and mysteriousness that have always drawn, enticed and soothed me. Backpacking and riding motorcycles or jeeps in the desert have been a big draw in my life and probably will always be. There were times when we finished our patrol in Eilat. As we arrived, tired and dust-coated from a long, rough day often with searing desert winds, we pointed our jeep straight for the beach. What a joy it was to plunge into the pure, cool, blue waters of the Red Sea. That sensation as I dove deep was a kind of ecstasy.

Patrolling the desert

My soul soothed by

Mountains of sand as far as the eye could see

A stillness, a magic in the arrid air I inhaled

A time to reflect

Turn inward and explore life in all of its wonderment

I was her

Out-Of-Body Experience & Its Life-Long Meaning

Then, as a 20 year old, still in the army, I was serving in the occupied Gaza Strip when I found myself, with eight of my soldiers, surrounded by a rapidly advancing, rock throwing crowd of young Gazans. For a split second, I had an out-of-body experience where I saw the scene from high above. In that mystified and astounding instant, I realized the two fateful/calamitous choices I had were to either save our lives by shooting at the young Gazans closing in on us, or to be harmed or even killed by them. Either way lay tragedy. Clearly neither choice seemed right. Thankfully, we were rescued by our troops at the last second; no shots were fired and no one was hurt. At that very moment, I knew that in order not to be confronted with such a situation (which is inherent part of an occupation) ever again, I would have to leave the country I loved, Israel. That day did not come for almost a decade when I went to the US to study.

I saw myself earily

Almost like a phantom

Hovering above a crowd of angry faces

Watching the scene unfold below

My life caught somewhere between

the living and the dead

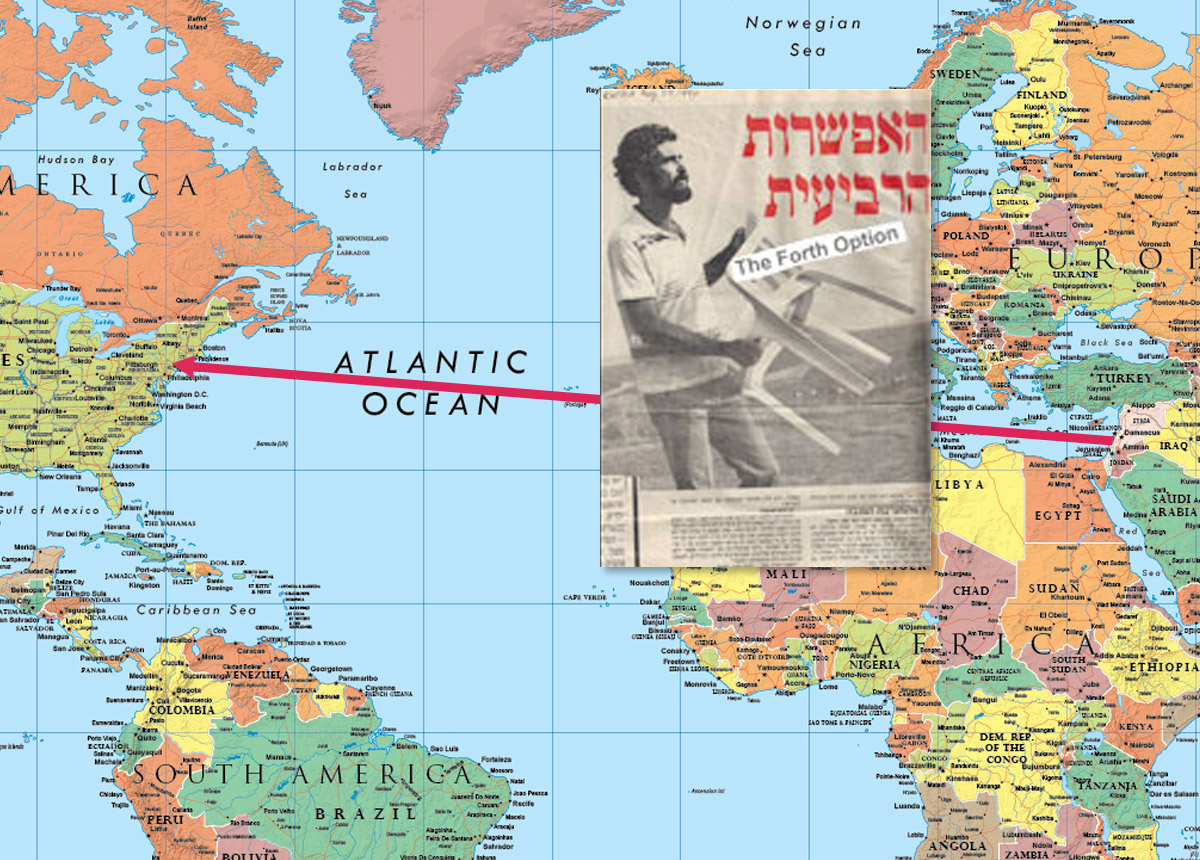

The Fourth Choice: On Leaving Israel

During a return visit to Israel in 1990, I was interviewed by the editor of “Chotam”, an Israeli newsletter, to discuss my culturally unpopular decision (at that time) to leave the country I loved (and still do), Israel. I mapped for him the three options I had if I were to have stayed and thus, however indirectly, have been party to the Israeli occupation of the West Bank: 1. As the Dissonance Theory predicts, I would have gradually become more right wing in order to justify my actions and my country’s immoral occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. 2. I would have become more politically involved in order to fight the occupation and promote peace and non-violent co-existence between Israel and its neighboring Arab countries, similar to what my sister did as part of Women in Black. 3. While keep hoping for peace, I would create and live in a bubble, not attending to the whole peace/war/occupation issue altogether… 4. None of these options were acceptable, so I chose a fourth option… to leave.

In other words, leaving Israel was partly related to my interest in avoiding acting like a “passive bystander” (i.e., bystander effect) in regard to the immoral Israeli occupation of the West Bank.

The choice, an objection, a dissent,

A moral decision to stand up against

the Israeli occupation of the West Bank;

Had been agonizing for me,

Leaving my homeland, the country I fought for

was wounded for, had risked my life to defend

My decision, culturally unpopular,

But morally correct

Sheriff of Tiran Island – Reversing Day & Night

Thinking back to my growing-up years, and including my military service, I can clearly trace the emergence of my fascination with all kinds of boundaries. A striking early example was when, as a young officer, I served on the remote, barren, but intriguing, Tiran Island, a strategic ‘bare giant rock’ in the Red Sea. My soldiers often referred to me as the “Sheriff of Tiran,” a title they painted on my small wooden ‘home.’ Besides taking care of the basic military duties, I spent much of my time wandering alone around this lifeless speck in the sea with my bare feet, a diving knife strips to my calf and a bathing suit and diving with friendly sharks and huge sea turtles. I found the island to have a profound and complex, spiritual nature. At that time, I was musing about the boundaries between day and night and wondered whether the distinct extreme separation of day and night is an artificial construct created by humans and their ancient cultures, or is it an inherent part of human nature. To satisfy my curiosity - and to the profound dismay of my soldiers - I experimented with inverting day and night by reversing our daily routines and the customary way of life of most humans and many animals living currently on the planet by ordering my soldiers (I was the only officer and highest ranking soldier on the island) to sleep during the day, eat breakfast at sunset, lunch at midnight and dinner at sunrise. While I was quite engrossed by my unorthodox research and the exploration of the nature of Man, I also noticed the resistance and outrage of my soldiers who perceived the experiment as seriously deviant. While not always popular, my questioning ‘common knowledge’ and our immemorial ways of living has been large part of my life story.

Exploring various social constructs

Night becomes day

A reversal of established norms

Questioning the order of things

A curiosity, welled up within me

A quest, an intellectual adventure

‘Kilometers Sex Chasers’ & ‘Hopeful Miles’

We were housed in a ‘quiet’ military base in the Arava desert area, by the Jordanian border, where Israeli male and female soldiers served alongside each other. It was 1970, I was a lieutenant and 2nd in command of the base and became good friends with Miri, (not her real name) an intelligent, gorgeous female soldier who was being consistently pursued by men of all ranks on the base. We developed a deep and fun relationship discussing how men were looking at her, making comments, inviting, suggesting, reaching out and touching her inappropriately.

As our friendship deepened, she shared with me the various ‘games’ she had been playing, in fact, toying with the male soldiers who pursued her. When they offered to take her for a spin in the desert in their Jeeps or other macho military vehicle, she would keep track of how far they each drove before they began to sexually pursue her until they finally, disappointedly, gave up, turned around, and drove back to the base. She described in rich detail how some started with sweet talking, while others reached straight for her breasts. Some pretended to be interested in her philosophy of life while others took a short cut straight to her crotch. We discussed the pursuers’ strategies and embellished it with fun mathematical (miles) precision.

We established a practice where she would record the vehicle odometer as soon as she entered the vehicle with any ‘hopeful pursuer,’ and then again when they returned to base. In our bemused conversations we ranked the soldiers and officers by their ‘hopeful miles’, i.e., how far they drove the vehicle before they gave up and turned back.

- The shortest distancers, most impatient ones, were nicknamed ‘the 5 kilometer (3 miles) impatient chasers’. Obviously, these were highly entitled and impatient men who were generally on the crude side.

- We named the next level ‘the 20 kilometers (13 miles) pretenders.’ They would take more time to drive and more effort to seduce her than the first group before they realized the futility of their aspirations.

- The most ‘persistent’ few were crowned ‘the 50 kilometer (30 miles) determined pursuers.’ This group drove 30 miles, some even off roads, before they gave up and turned back. These 30 mile insistent pursuers sometimes read her poetry, confessed their longtime attraction to her, and romantically pointed at the stars, moon, mountains or an occasional nocturnal desert animal. Their patience generally wore off at 20 miles and poetry would often shift to an aggressive sexual touch around mile 25 to 30.

Obviously, we paid careful attention to her physical safety in these ‘adventures’, primarily by sorting out ahead of time who she agreed to run the ‘miles experiment’ on. She also had her own small military radio on her (in that pre-cellphone era) where she could, if necessary, directly connect with me and I could track her physical location.

She never had sex with any of the hopeful pursuers. It was a game that some may legitimately claim was unfair, unkind, manipulative or even cruel… It may come as no surprise to some that she and I never physically sexualized our friendship. Obviously, our measuring games, ranking the officers and soldiers by their hopeful miles and follow up conversations were rather sexy in and of themselves. In fact, one may say, it was as sexy as traditional sex… if not even more…

In the Merchant Marine - 2nd Out-Of-Body Experience

After my land-bound military service, I embarked on the life of a sailor aboard a commercial freighter. Joining the Merchant Marine as a cadet, I learned the ways of the sea, the ancient art of navigating by the stars, and the many skills, rites and rituals of seamanship. The ship dropped anchor in such European ports as London and Antwerp - all of them blessedly far from military camps and battlefields! Besides learning the officers’ roles and responsibilities, I found it a most interesting anthropological journey into the life of sailors. On my last trip back to the port of Haifa, a long-simmering, mutual antipathy between the boatswain and me erupted into a ferocious fist fight on an enclosure resembling a boxing ring on the very front deck. As we fought, I had my second out-of-body experience; a part of me seemed to rise up and up to the level of the distant wheelhouse. From there, far below and ahead, I saw these two, tiny figures, like stick figures in a cartoon, ferociously, brutally and meaninglessly fighting each other, with the soft, calm sea around us. It was a singularly odd experience to be simultaneously engaging in the violent, physical fight and also observing the scene from high above, in all its utter senseless stupidity. In that instant, philosophy aside, I realized the two choices I had were to either determinedly defend myself or be thrown overboard, with a good likelihood of drowning. The fight resulted in a broken nose for me and swollen-shut, black eye for him. The senselessness and absurdity of the fight and the out-of-body observing-self stayed with me for a long time. Nonetheless, that sailing experience touched my fate, igniting an abiding interest in the sea which brought me to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where received B.Sc. in chemistry and, more significantly, completed few graduate courses in oceanography, which became my next career.

Under a black curtain of sky

With stars twinkling above our heads

On a ship I sailed to faraway lands

To Antwerp and London

Once I observed a fight with the boatswain and I

Hovering above the earth I witnessed our exchange of fists

A true out- of -body experience

The life of a merchant marine

A new love of the sea born in me

Hebrew University in Jerusalem & ‘Pre-Meeting’ my Wife

In parallel with my immersion in my scientific studies, I could not help but be moved by living in the west part of the ancient city of Jerusalem, at the nexus of three major spiritual traditions. I lived in a beautiful old house in the Coptic Church compound. One Christmas Eve, I was mysteriously drawn to my motorcycle and headed out into the still night. Randomly driving through the Judean Hills beneath the stars, I found myself… where else?… but, Bethlehem. Then, neither randomly nor consciously, for the first time I magically ‘met’ my future beloved wife, Jenji, as she was right there (15y.o.), also attending the Christmas Eve Mass with her family at Manger Square in… Bethlehem. We connected the dots on this miraculous and synchronistic chain of events about 20 years later when we ‘met again’ when she (again, non-randomly) was the ballet teacher of my daughter, Azzia, in Sonoma, CA.

A magical moment

Under stars that dotted the black sky above the Judean Hills,

I arrived in Bethlehem

At a Christmas Eve mass where

My beautiful and precious future wife stood

We were both together, the fates aligned

And our constant love for each other was magically set in motion

Sacredness of Jerusalem - Absorbing the Magic

My time attending Hebrew University in Mount Scopus, Jerusalem (1972-1975), studying chemistry and oceanography, was one of my most profound and powerful spiritual awakenings, as Jerusalem embodied the convergence of three major religions. It was at this time that I experienced one of my most profound and powerful spiritual awakenings. In addition to studying, socializing, and playing college basketball, I drove a taxi on the weekend. This was not only anthropologically fascinating but also helped me discover the beauty, complexities and the multi spiritual nature of Jerusalem.

My soul danced like glitter in the wind,

as I embarked on an academic journey,

to study the oceans and chemistry

My mind adrift in a certain enchantment,

as if lit by a thousand tiny candles

A sacredness, a time for deep contemplation

On Being a Cab-Driver… I Mean a Psychologist

During my undergraduate studies at the Hebrew University, one of the more intriguing and valuable experiences in my life was the exposure that I had to a wealth of human experience while a cab driver in Jerusalem. It was an anthropologist’s dream. Customers waved my cab down and hopped into the back seat of the cab. Once in the cab, many of them (consciously or unconsciously) realized that it was a unique setting where they could fully trust the privacy, confidentiality, and most importantly the anonymity that the cab ride and my attentive, curious ears provided. Knowing that they had only a short time in the cab, they talked fast and revealed and shared a huge spectrum of rich human experience with me. Most of the stories were about lovers who betrayed them, parents who hurt them or friends who violated their trust. Then, some excitedly talked about upcoming weddings, marital affairs, graduations or spectacular adventures. Some tourists were pleased to realize that I spoke English fluently and proceeded to request a tour of old Jerusalem, Masada, the Dead Sea or the Sea of Galilee. I was happy to serve as their tour guide. While most people paid the full fee for the ride and happily added tips, on the rare occasion some flashed a knife or even a hand gun when I gave them the price. Others had unusual requests, such as an ultra-religious man who laid down in the back of the cab in order to avoid being seen, and asked me to take him to a prostitute where all he wanted was to touch her . . . thigh. Without a doubt this rich engagement with people, fantastically prepared me for my career as a psychologist.

Laughter and hushed conversations

like incense that lingers in the air stories

echoed about lovers and family,

a snapshot into the lives of ordinary people,

my ears thrilled to learn about their rich experiences

My career as a psychologist,

like a brush fire in the wind,

ignited by excited tales in a cab.

Against Medical Advice (AMA)

Over the years, when I have said or done something stupid, someone invariably has replied, “What! Did you hit your head?” Well, yes, actually several times ☺. During my three years of studying in Jerusalem I had the honor of leaving the hospital AMA (Against Medical Advice) several times following emergency hospitalizations, most of which involved motorcycle accidents. I vividly remember one accident when I was coming down from the Mt. Scopus Campus of the Hebrew University on my powerful BMW bike on a Saturday, being knocked backward by a thin, almost invisible, wire that the ultra-orthodox religious Jews (aka. ‘black-hats’) had put across a road that wound down from the Mt. Scopus. The wire, which was strategically placed there to ‘punish’ the ‘non-believers’ who travel on the Sabbath, hit the front of my neck, while the bike continued to go forward, leaving me hanging on the wire by my throat. To this day, I wonder how I survived this accident and how I could leave the hospital against medical advice. (There may be God after all 😃). Similarly, I have been puzzled about how I miraculously survived another accident where I lost my lights on the bike but nevertheless was determined to ride to my ‘not-to-be missed’ basketball practice with my college basketball team. It was dark and rainy and it is no wonder that riding the bike on a narrow, wet road without lights ended up with me being rescued from a deep and flooded ditch by the side of the road at the bottom of one of Jerusalem’s steep slopes. Both incidents, as did some others, ended with AMA departures from the hospital within a few hours of admittance, concussions and all.

I wonder how often I’ve trusted my Gut,

my own instincts,

to know instinctively that I’d be okay

Against Medical Advice

Dare & Trust! - Perhaps my mottos

To challenge the Medical Industrial Complex

With my own desire to live freely & fully

Playfully Challenging The Incest Taboo

Part 2: War - Oceanography - Diving

Part 3: Adventures in Africa - Europe

Part 4: Psychology of War - Psych of Victim - Family

Part 5: Contributing to the Field of Psychology - Travel/Adventure

Part 6: More Family - Travel/Adventure - End of Life - Teaching

Part 7: Writing - Family - More Adventures - More 'Doing Good' to 70 y.o.

Part 8: Next Stage in life 70+ y.o.

Part 9: Amazement! I am still here

Before exploring ‘life after leaving,’ I want to revisit my time in Israel in the early 70s as an officer in the Israeli army. Our highly trained unit was stationed in a tremendously overcrowded, poverty-stricken, and polluted refugee camp in the occupied Gaza Strip. The camp consisted of thousands of single-story houses jammed full with multiple generations in families, and often chickens and ducks as well! The narrow streets—actually muddy alleyways—emitted the foul stink of urine and excrement from donkeys, mules, chickens, ducks and… humans.

Before exploring ‘life after leaving,’ I want to revisit my time in Israel in the early 70s as an officer in the Israeli army. Our highly trained unit was stationed in a tremendously overcrowded, poverty-stricken, and polluted refugee camp in the occupied Gaza Strip. The camp consisted of thousands of single-story houses jammed full with multiple generations in families, and often chickens and ducks as well! The narrow streets—actually muddy alleyways—emitted the foul stink of urine and excrement from donkeys, mules, chickens, ducks and… humans. I despised myself for not protecting this woman and her children, for not standing in front of the Israeli bulldozer the way the heroic ‘Tank-Man’ stood in front of the tanks in Tianaman square in China.

I despised myself for not protecting this woman and her children, for not standing in front of the Israeli bulldozer the way the heroic ‘Tank-Man’ stood in front of the tanks in Tianaman square in China.