Stepping into the Void – On Being a Paratrooper

The Israeli army is a rite of passage for almost all young Israelis and during my service I faced barriers and boundaries that I had never before encountered. I was a paratrooper and I will forever remember the first time I stood at the launch door of an airplane, thousands of feet above the earth – poised at a fundamental boundary between the real and the ethereal – and stepped forward into the void. It was a transforming experience, fraught with suspense and fear but also imbued with joy and the instant dawning of a new perspective. Floating, falling, what a metaphor for Life! – but also entrusting my life to a slip of silk, certain that the canopy would open, trusting to the unknown.

A door separated me from

airplane and sky

One foot placed gingerly on a metal floor,

And the other foot on a cloud

Holding on, letting go

Sailing through whisps of white

Cottonball clouds

Floating endlessly above the earth

Gliding gently below.

Looking at Death Straight in the Eyes: An Encounter w/ Death

Soon after, as a lieutenant and combat officer, just 19 years old, viewing life as a prism of possibilities, I found myself at the greatest boundary of all, that of life and death. For the first time, I held a soldier’s dead body in my arms. Simplicity and innocence vanished and once again a new perspective opened before me, a new consciousness. I felt so profoundly the preciousness, the fragility of life and the importance of living each day fully, with care and integrity, as if it were my last day on earth. To this day, I try to live that way.

Life with its infinite possibilities

Could vanish without warning

Cradling a soldier’s dead body in my arms

Mourning a life taken too soon

A new perspective formed in my consciousness

An appreciation for each day

As it could be my last

Shooting the Light Bulb – How Dumb is That?

While some boundaries are physical, existential, or spiritual, others are developmental, metaphorical, or metaphysical. I remember a time, during my military service, when three of us, all officers, were housed in a cement bunker. Late one night, we were all very tired and had turned in for a good night’s sleep. I was already in bed and, instead of doing the obvious of getting up and turning off the light switch, I reached for my handgun and shot out the single light bulb hanging from the ceiling. While I accurately hit the bulb, which effectively turned the light off, the bullet ricocheted wildly around the cement walls for what seemed like a very long time, seriously endangered the life of all three of us. On my list of boundaries, this would easily rank as a highly reckless, stupid, and an utterly irresponsible way of pushing boundaries – and fate.

The bullet ricocheted throughout the room,

after initially piercing the air,

and making the room change from light to dark

In the moment, the only murmur was my heart

Which grew louder, telltale heart, like from Poe,

I had risked their, our… lives

I was her

Out-Of-Body Experience & Its Life-Long Meaning

Then, as a 20 year old, still in the army, I was serving in the occupied Gaza Strip when I found myself, with eight of my soldiers, surrounded by a rapidly advancing, rock throwing crowd of young Gazans. For a split second, I had an out-of-body experience where I saw the scene from high above. In that mystified and astounding instant, I realized the two fateful/calamitous choices I had were to either save our lives by shooting at the young Gazans closing in on us, or to be harmed or even killed by them. Either way lay tragedy. Clearly neither choice seemed right. Thankfully, we were rescued by our troops at the last second; no shots were fired and no one was hurt. At that very moment, I knew that in order not to be confronted with such a situation (which is inherent part of an occupation) ever again, I would have to leave the country I loved, Israel. That day did not come for almost a decade when I went to the US to study.

I saw myself earily

Almost like a phantom

Hovering above a crowd of angry faces

Watching the scene unfold below

My life caught somewhere between

the living and the dead

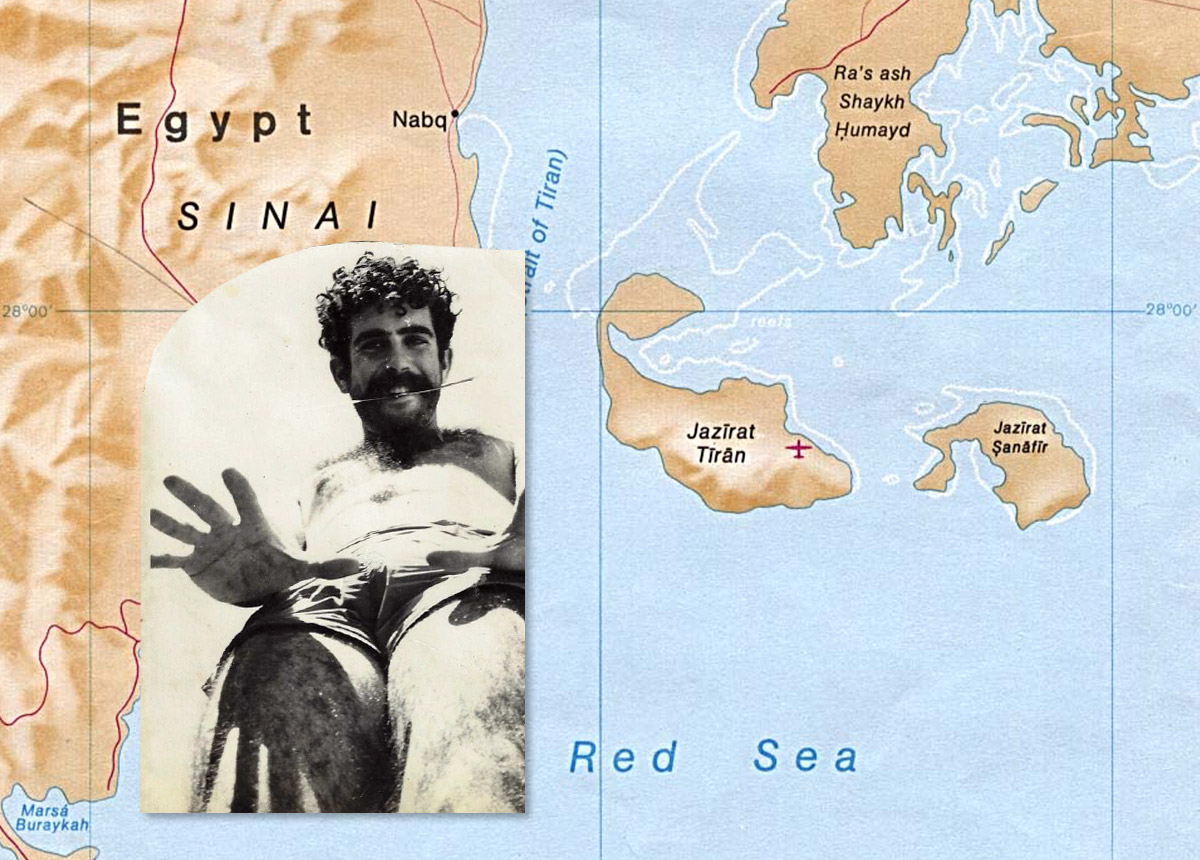

Sheriff of Tiran Island – Reversing Day & Night

Thinking back to my growing-up years, and including my military service, I can clearly trace the emergence of my fascination with all kinds of boundaries. A striking early example was when, as a young officer, I served on the remote, barren, but intriguing, Tiran Island, a strategic ‘bare giant rock’ in the Red Sea. My soldiers often referred to me as the “Sheriff of Tiran,” a title they painted on my small wooden ‘home.’ Besides taking care of the basic military duties, I spent much of my time wandering alone around this lifeless speck in the sea with my bare feet, a diving knife strips to my calf and a bathing suit and diving with friendly sharks and huge sea turtles. I found the island to have a profound and complex, spiritual nature. At that time, I was musing about the boundaries between day and night and wondered whether the distinct extreme separation of day and night is an artificial construct created by humans and their ancient cultures, or is it an inherent part of human nature. To satisfy my curiosity – and to the profound dismay of my soldiers – I experimented with inverting day and night by reversing our daily routines and the customary way of life of most humans and many animals living currently on the planet by ordering my soldiers (I was the only officer and highest ranking soldier on the island) to sleep during the day, eat breakfast at sunset, lunch at midnight and dinner at sunrise. While I was quite engrossed by my unorthodox research and the exploration of the nature of Man, I also noticed the resistance and outrage of my soldiers who perceived the experiment as seriously deviant. While not always popular, my questioning ‘common knowledge’ and our immemorial ways of living has been large part of my life story.

Exploring various social constructs

Night becomes day

A reversal of established norms

Questioning the order of things

A curiosity, welled up within me

A quest, an intellectual adventure

‘Kilometers Sex Chasers’ & ‘Hopeful Miles’

We were housed in a ‘quiet’ military base in the Arava desert area, by the Jordanian border, where Israeli male and female soldiers served alongside each other. It was 1970, I was a lieutenant and 2nd in command of the base and became good friends with Miri, (not her real name) an intelligent, gorgeous female soldier who was being consistently pursued by men of all ranks on the base. We developed a deep and fun relationship discussing how men were looking at her, making comments, inviting, suggesting, reaching out and touching her inappropriately.

As our friendship deepened, she shared with me the various ‘games’ she had been playing, in fact, toying with the male soldiers who pursued her. When they offered to take her for a spin in the desert in their Jeeps or other macho military vehicle, she would keep track of how far they each drove before they began to sexually pursue her until they finally, disappointedly, gave up, turned around, and drove back to the base. She described in rich detail how some started with sweet talking, while others reached straight for her breasts. Some pretended to be interested in her philosophy of life while others took a short cut straight to her crotch. We discussed the pursuers’ strategies and embellished it with fun mathematical (miles) precision.

We established a practice where she would record the vehicle odometer as soon as she entered the vehicle with any ‘hopeful pursuer,’ and then again when they returned to base. In our bemused conversations we ranked the soldiers and officers by their ‘hopeful miles’, i.e., how far they drove the vehicle before they gave up and turned back.

- The shortest distancers, most impatient ones, were nicknamed ‘the 5 kilometer (3 miles) impatient chasers’. Obviously, these were highly entitled and impatient men who were generally on the crude side.

- We named the next level ‘the 20 kilometers (13 miles) pretenders.’ They would take more time to drive and more effort to seduce her than the first group before they realized the futility of their aspirations.

- The most ‘persistent’ few were crowned ‘the 50 kilometer (30 miles) determined pursuers.’ This group drove 30 miles, some even off roads, before they gave up and turned back. These 30 mile insistent pursuers sometimes read her poetry, confessed their longtime attraction to her, and romantically pointed at the stars, moon, mountains or an occasional nocturnal desert animal. Their patience generally wore off at 20 miles and poetry would often shift to an aggressive sexual touch around mile 25 to 30.

Obviously, we paid careful attention to her physical safety in these ‘adventures’, primarily by sorting out ahead of time who she agreed to run the ‘miles experiment’ on. She also had her own small military radio on her (in that pre-cellphone era) where she could, if necessary, directly connect with me and I could track her physical location.

She never had sex with any of the hopeful pursuers. It was a game that some may legitimately claim was unfair, unkind, manipulative or even cruel… It may come as no surprise to some that she and I never physically sexualized our friendship. Obviously, our measuring games, ranking the officers and soldiers by their hopeful miles and follow up conversations were rather sexy in and of themselves. In fact, one may say, it was as sexy as traditional sex… if not even more…

On Being a War Hero – Groomed to Sacrifice

The messages drifted in, almost like elevator music entering my subconscious mind, such good food for the developing ego “Be a man! Be admired! Be a war hero.” As a skinny young boy, I recall standing a little bit taller, sticking my chest out a bit more and imagining basking in the admiration of women and children. I was destined to be a war hero! We were groomed to sacrifice. I was 23-years-old when the 1973 war between Israel and the surrounding Arab countries started with a massive surprise attack on Israel. Israel—the country my parents wove every hope and dream into, the post-holocaust safe place for the children of our tribe and the generations to follow. Invaded by the surrounding Arab countries from the north, west, and south, Israeli casualties were mounting fast and a sense of panic and terror engulfed the country. All reserve soldiers were immediately called for military service. I was strongly torn. On the one hand, I believed then and still do, that Israel has the right to exist and obviously has the right to defend itself. This being a given, I felt I should join the armed forces to fight for Israel’s very survival. On the other hand, I also strongly believed that the war could have been prevented if Israel had given back (as it should have) the occupied territories that it had conquered in the 1967 war. But on yet ‘another hand’ I wanted to be a war hero. I did not want to stay behind with the women, children, the elderly and disabled. So in the end, even though I was not drafted or called to serve, I was strongly compelled to join the armed forces fighting for Israel’s survival, in a war that could have been avoided. At my own initiative I was assigned to a highly esteemed paratrooper unit. Following that initial egoic impulse, I became a war hero.

I was groomed to serve a country

a land where Jews re-planted roots

Together grown from springs of hope

And tenacity

Yet torn was I, the desire to be a hero

But to sacrifice myself, some of my values

Made question my identity, my sacredness

My country’s vision, my vision of self

Breaking Up With My Girlfriend So I Would Be Free to… Die

The highly trained paratrooper unit, in the 1973 (Yom Kippur) war, that I was part of was stationed by the Sea of Galilee because Central Command did not know where it wanted to deploy us. The Israeli army was sustaining severe casualties to soldiers, as well as damage to tanks and armed vehicles as a result of the new shoulder rockets supplied to the Egyptian army by the Soviets. Knowing that the central command was going to deploy us to one of most dangerous combat areas, there was a heightened likelihood of dying or being severely wounded in battle. Knowing this, I decided to break off my two-year relationship with my dear, sweet, loving girlfriend. As odd as it sounds in retrospect, at the time, I did so for what I considered to be two clear reasons: First: I wanted to be able to go to battle and face bullets, bombs and… death without needing to think of or worry about who I was leaving behind. It meant to me that I was free to die. It seemed to me that if it came to that it would help me face the bullets and die in peace. Second: I thought it was the most loving and unselfish thing to do, as it would free my girlfriend from worrying about me since we would no longer be lovers. Needless to say, this peculiar way of thinking, as many have pointed out to me later in life, was one more manifestation of my eccentric way of doing the ‘right thing.’ Nevertheless, at the time, it did give me a true sense of freedom to face death head-on without fear, hesitation or worry. I later learned how broken-hearted and upset my girlfriend was with my odd way of thinking and of loving, by breaking off the relationship in order to ‘protect her.’

It was my way, to face death

Head on, to protect

Those I loved and spare them from any hurt or pain

To leave her would enable me to

Fight and not have my girlfriend

Worried about my safety and well-being

That she could be protected from fear

I could fight, by doing good

And the right thing

Discovering the Power of Women on the Male Psyche

As we were waiting to be deployed in the 1973 (Yom Kippur) war, I noticed that almost all my fellow officers were impatient to engage in battle even though it was clear that doing so was likely to result in high casualties to our unit – and, of course, to ourselves. In fact, some men even tried to exert influence on the high command to get us deployed. Believing that the war could have been prevented, I was more ambivalent. I felt spacious with time in our ‘wait and see’ position by the gorgeous Sea of Galilee, and wondered what the soldiers were actually thinking in anticipation of being at war and at risk for their lives. So I started questioning soldiers about their attitude, and almost of all of them said they unequivocally wanted to engage in battle, regardless of the high probability of injury or death. As soon as I realized this, I went out again, this time with my notebook, asking the bored and anxious ‘to-be-deployed’ soldiers why they were so eager to go to war and risk their lives. Aside from the cliché response of wanting to defend the country, when I invited them to go deeper most of them said they did not want to come back home without a war story. Now my curiosity skyrocketed and the researcher in me could not wait to go back and ask the soldiers, “Who is this story for?” The response took me completely by surprise. They did not want to come back home without a war story to tell their wives, sweethearts and girlfriends. It was a truly (personal and academic) ‘aha-moment’ realizing the invisible powerful presence of women among the battle-ready paratroopers, such that they were willing to risk their lives rather than come home without a story of heroism of some sort.

As an analyst, even then,

I researched the behavior

of the soldiers who I commanded

and asked:

why are you risking your lives to go to war?

The answer they gave was baffling.

The story the soldiers told me

was they did this for women,

whose presence permeated the air,

who contributed to the war effort,

more than I ever surmised or thought possible.

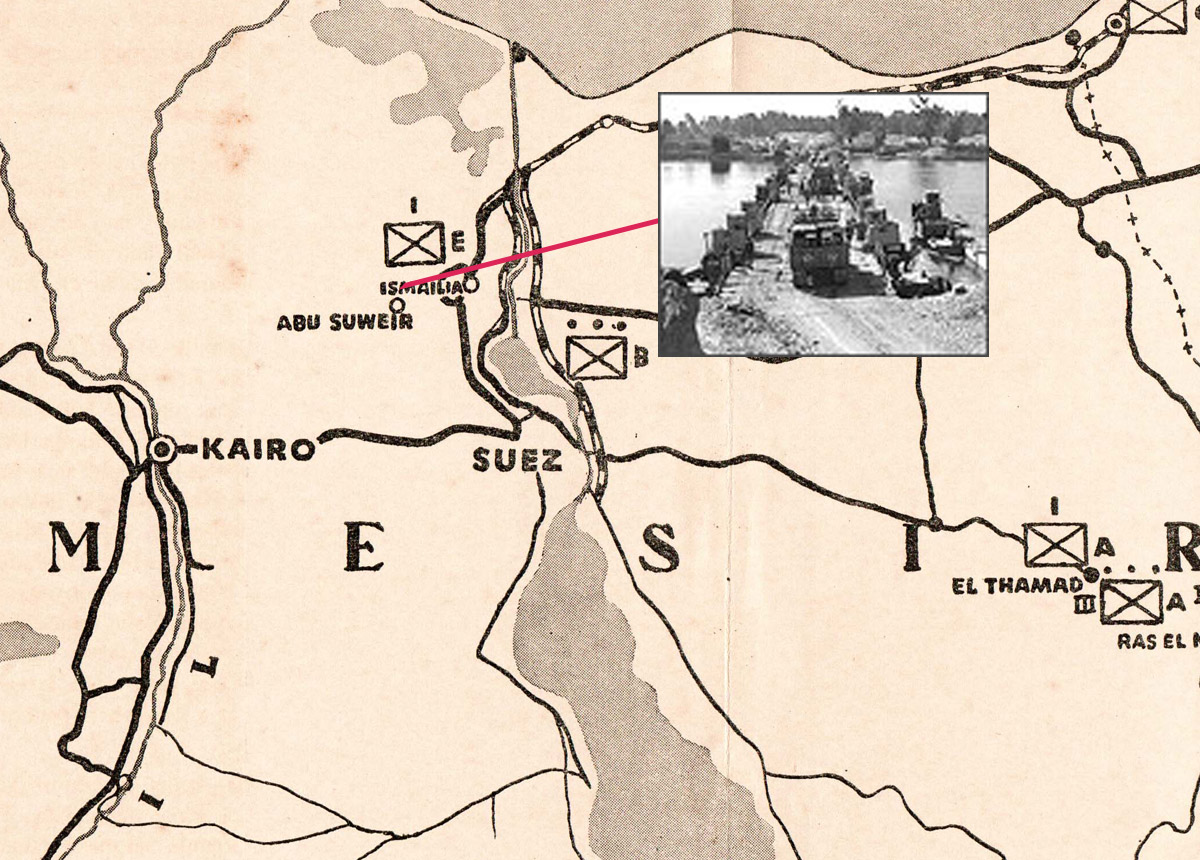

Thumbing My Nose at Death on a Bridge of Fire

Towards the end of the 1973 war, my unit was finally deployed. We were assigned to cross a bridge across the Suez Canal and head north towards the revered city of Ismailia. At this point of the war the Egyptian army was highly concerned that if the Israeli Armed Forces crossed the Suez Canal, they would subsequently have a clear path to Egypt’s capital, Cairo. As a result, the Egyptian army was defending the bridge that my unit had been assigned to with all their remaining military might, relying on intense artillery bombardments, air force bombings, and anti-tank guided missiles to deter the incoming Israeli army. When we arrived, Israeli tanks, personal carriers and jeeps were on fire and literally flying off the bridge. It was an intense game of chicken between the Egyptian bombings and the Israeli military engineering unit, which was rapidly rebuilding and repairing the repeatedly hit and damaged bridge. Amazingly they were able to keep rebuilding despite the catastrophic losses they were suffering.

Then, I received my orders: we were commanded to cross this fiery strip and move deeper into Egypt. While the rest of my unit quickly jumped into vehicles and sped as fast as they could into the clouds of smoke that covered the bridge, my recklessness, bravery and perhaps my stupidity spurred my buddy and me to cross this death zone by foot. As fire and metal rained down around our unprotected bodies, we sarcastically argued over who would be the first to die, and who would get to put a wreath on the grave of the other at the prestigious famed national military cemetery on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem. Halfway across the bridge I suddenly felt compelled to stop. A strange sense of calm and quiet came over me despite the deafening bombs and missiles exploding all around. Almost engulfed by the chaos and destruction, I looked up at the sky and extended a defiant middle finger to God, a gesture by which I was telling Death, “I do not fear you!”

This attitude of fearlessness towards death, which has harmoniously and consistently coexisted with my deep reverence for life, has revealed itself in multiple ways throughout my life, such as in my predilection for evacuating hospitals against medical advice, diving the magical but lethal Blue Hole, shooting the light bulb, challenge-riding a motorcycle at the Himalayas by 4,000ft drops and many other death-defying ventures. My mother vowed she wanted to ‘die erect,’ so perhaps there’s a strain of this mentality I inherited from her!

Even as I walk, surrounded by flames

On this Bridge of Fire

You, death, will not win!

Though you may try to burn my aching body

You will never singe my soul – my essence

Oh death, You will not defeat me!

Monkey & Me: Respect For & Identification With the Enemy

After a few days of cautiously moving towards enemy lines in the 1973 war, our military unit became the target of artillery shells. Some fell to the left of us, some to the right, some in front of us where we were headed, and some behind us, where we had been an hour ago. In a curious, fascinating, and yet terrifying pattern, the shells began to gradually close in on us in a perfect lethal circle, closer and closer on all sides. As our unit paused under a grove of high palm trees, the shells began falling so close to our group that it became obvious that the artillery weapons were being systematically directed by someone or something that was aware of our location. Was there an unseen aircraft tracking us, a satellite, or an eye in the sky?

As we frantically tried to figure out who/what was doing this we peered at the sky through the fronds of the palm trees above and suddenly spotted what in some military jargon is called a “monkey” — a perfectly camouflaged Egyptian soldier sitting atop one of the trees, trying to blend in with the thick canopy. We instantly realized that he was the one providing his fellow artillery soldiers miles away with the exact location of our unit. Within a milli-second, about 20 to 30 solders aimed and rapidly shot their M-16’s automatic guns at him. By the time he hit the ground he had several hundred bullet holes in him. Needless to say, he did not suffer much. A couple of distressed, frightened and enraged soldiers even shot a few more rounds into the lifeless bleeding body.

I looked at this bullet-ridden corpse and experienced an upwelling of admiration, respect, and even awe, for this man who had directed his artillery on our unit… and in the end, on himself. I considered how he had been deliberately and consciously ready to face death in defense of his country, just as I had been a couple of days prior while crossing the bridge of fire. My feelings of identification and admiration were not shared by my fellow soldiers. In fact, a fellow officer rushed toward the body and took the bayonet off his gun, both as memorabilia and as an attempt to humiliate the enemy. I was unexpectedly overcome with rage and hatred towards this man’s lack of acknowledgement of the bravery of the monkey. I instinctively wanted to protect his body, and at the bare minimum, have our unit spend a few seconds around it to honor the complex relationship that we had with our enemy. I did feel hatred towards the threat he had posed to myself and my soldiers, yet I also was touched by his sacrifice and courage. I was very aware that I could have been the one to be riddled with bullets just a couple of days earlier on the bridge.

In effect, this is what we soldiers are about: walking the tightrope of potential sacrifice while defending our country as heroes. Yet, I suspected that the monkey, like me, had not viewed his defiance of death and willingness to sacrifice as particularly brave or heroic. Rather, his act was a way to embrace life in its fullest. Ironically, saying ‘Yes to life’ meant also saying ‘Yes to death.’

I identified and could understand

the role of the monkey

a soldier who provided his artillery soldiers

with the location of our unit

That he had been willing to die

and willingly sacrificed himself,

without fanfare,

as part of the greater ecosystem of life

and for his country.

This Moment Could be My Last

We survived, at least physically, the crossing of the bridge over the Suez Canal under rain of fire in the 1973 (Yom Kippur) war and the close call with the monkey aiming the artillery on us. Getting closer to our target city of Ismailia, my buddy and I were driving a jeep on a mission in coordination with a sister unit when we lost our bearings and shockingly found ourselves behind enemy lines. There, suddenly and unexpectedly we arrived at a most horrific, eerie sight. In front of us were the widely scattered remains of an Israeli army jeep which had literary evaporated, annihilated into thin air when struck by a lethal Egyptian anti-tank missile. We also stumbled upon the tiny dog-tag, all that was left from an Israeli soldier whose body, like most of the parts of the jeep, had vanished into the same thin air.

Realizing that the jeep we were driving was situated exactly where the evaporated jeep once stood was a surreal experience. We knew that in no time, at any given moment and without warning, we too could vanish and annihilated just like the passengers of the other jeep. We exchanged looks of awe mixed with wonder and horror. As we silently and with full presence inched our way back to our unit, we struggled to metabolize the very real possibility of our instantaneous annihilation and death. Thinking of being evaporated in an instant felt very different than considering dying by a bullet. This really drove home how we had neither control of our destiny nor predictive power as to what might be awaiting us. I truly got it how life, and its continuance, is such a mystery, and ultimately, such a gift.

The scattered remains of an Israeli army jeep

A single dog tag

all that was left of a fellow soldier

In an instant death

could tap her cold, bony fingers

Against our shoulders

And in that unreal moment

Life suddenly became more sacred

When my Calf was Blown Off in Battle of Ismailia: Am I a War Hero or My Parents’ Sacrificial Lamb?

In the waning minutes of the Yom Kippur (1973) war, I once again found myself at the aweinspiring boundary between life and death during the Battle of Ismailia when I was seriously wounded after most of my left calf was blown off and I collapsed in complete and utter silence. The silence, as I put together months later, was partly due to the fact that I lost my hearing when the intense enemy bombing ruptured my eardrums. As soon as I collapsed into this zone of silence and injury, as if someone had literally pulled the rug from underneath me, I told myself, “I lost my leg because I should have not gone (or walked) to a war that I did not fully believe in.” (Later in life I followed up on this interpretation and explore in depth the constructs of the ‘metaphor of illness’ or the meaning of dis-eases.)

I was evacuated under heavy fire, and to my deep distress found myself in an armed vehicle, which I knew to be an easy target for the enemy’s lethal shoulder missiles. What was strange about the morphine-induced delirium I experienced during this evacuation was that I became less worried about being blown up by a lethal Egyptian shoulder missile than I was about being part of an imaginary ‘cosmic play,’ in which I was the sacrificial lamb to my peace-loving parents who were simultaneously and paradoxically against the war while proud of their ‘sacrificial hero/wounded lieutenant son.’ Years later, in an attempt to make sense of this bizarre but intriguing experience, I devoted considerable time to exploration of what is known as the Medea Complex, or the unconscious wishes of parents to kill their children as manifested by the 25 years (one generation) average of war cycles in modern times.

War hero, sacrificial lamb

In a war I did not fully believe in

My left calf, blown apart

Like the peaceful beliefs that had been planted,

like tulips in my heart

The world around me, sounds, colors

Faded in, briefly

My life, my being, my very essence

My fate, left in the balance

Between the desert and the cosmos

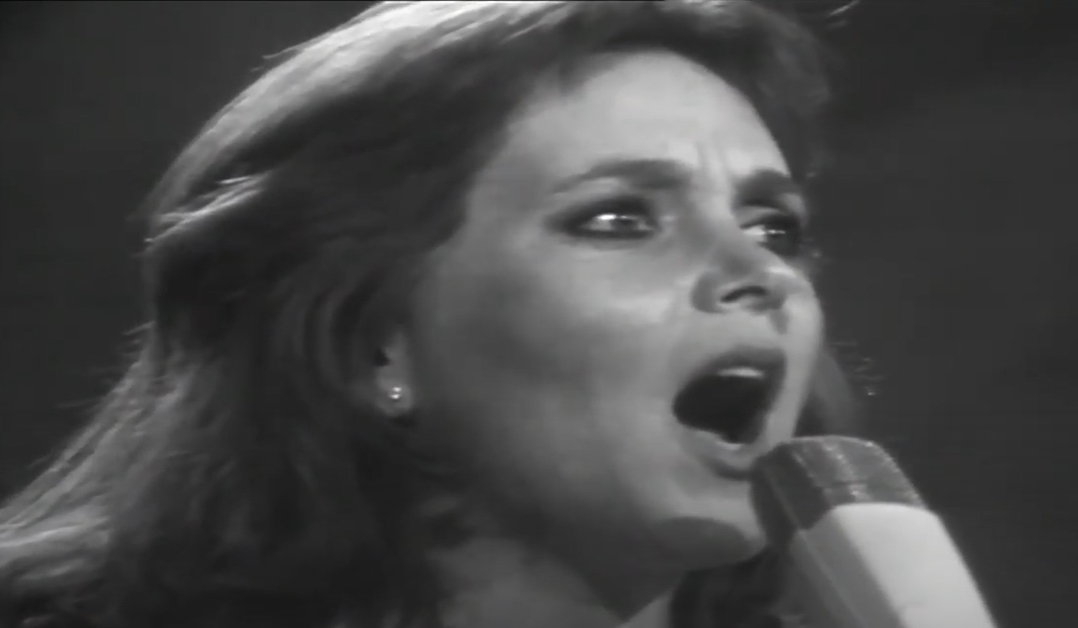

Song for Peace – Shir Lashalom

The powerful protest Song for Peace, a first of its kind in Israel, was sung for the first time in 1968, a year after the “Six Days war” was won, to a nation still drunk on victory. It premiered in my basic training boot camp by Miri Aloni and Lehakat Hanchal להקת הנח”ל [Lyrics: Yankele Rotblit; Melody: Yair Rosenblum; Complete lyrics & translation.

Bold, pacifist, and uncompromising, it touched many of us deeply at the time, and ever since, with its fearless message. It calls for the victorious people, and its army, to let go of the dead, to stop idealizing them, to stop the fighting on their behalf (in an endless cycle of death and wars), to stop whispering a prayer for peace, and instead to actually, yell it out loud and more importantly, bring it on!

50 years later, both the song and its potent message still reverberate in my body whenever I hear it, or sing it along.

Song for Peace

Let the sun rise

the morning give its light

The purest of prayers

will not bring us back

He who’s candle was snuffed out

and was buried in the dust

bitter cry wont wake him up

and wont bring him back

Nobody will bring us back

from a dead and darkened pit

here, neither the victory cheer

nor songs of praise will help

שיר לשלום

תנו לשמש לעלות

לבוקר להאיר,

הזכה שבתפילות

אותנו לא תחזיר.

מי אשר כבה נרו

ובעפר נטמן,

בכי מר לא יעירו

לא יחזירו לכאן.

איש אותנו לא ישיב

מבור תחתית אפל,

כאן לא יועילו

לא שמחת הניצחון

ולא שירי הלל.

The silent prayers for us

Like balloons released towards the heavens

The dead who died fighting will not

return, will not roam the earth again

Will not laugh or cry

If you honor us

Instead of singing songs

Use your voices to shout for peace

To stop endless wars that take your loved

ones to dark graves void of light

I was a boy – Lahakat Hanahal; להקת הנח”ל – הייתי נער

An equally powerful song that has stayed with me since my youth, and is likely to linger for the rest of my life is I was a boy also sang by Lahakat Hanahal. Lyrics: David Atid; Melody: Yair Rosenblum; Translation: DeAnna L’am

Heart-breaking and beautiful, the song captures the lifelong permanent damage suffered by millions of (the best of the best) young men who have been routinely, every generation, recruited to fight wars all over the world in the past 10,000 years. I am among those millions who were indoctrinated to fight to the bitter end, and to sacrifice our lives for the, often, senseless causes of our leaders, parents, as well as variety of economic forces, including the obvious, military industrial complex.

One of my dissertation topics was: “The Medea Complex and the Cycle of war” where I intended to explore the fact that wars, on average, take place globally in 18-22 years cycles, which is, like Medea who killed her children, the older generation sends the younger generation to war where the ‘best die first’ thereby the challenge to the older generation’s authority and power is significantly reduced.

The Rolling Stone powerfully attempted to address the same ‘post (Vietnam) war’ dynamic in their forceful song I want to paint it black.

Generally, ‘we’, young soldiers are barely 18 years old when we go to war to inflict destruction and to readily meet death: of our brothers, of the “other”, and possibly our own. This song potently describes all that we lost in the process: life, energy, power, innocence, trust, the ability to love, and perhaps most importantly the excitement and exuberance of our adolescence.

I was a Boy

The targets are cleansed and destroyed

Snow on mount Hermon melts in the sun

In a ghost town on the Golan Heights

A lonely donkey is lost like before the war

Summer returned to its old strongholds

But your face, my boy, remains changed.

Curtains and window blockers were removed

The city clerk locked the bomb shelters

Grasses climb and grow

Fresh greenery over scabs and canals

Pomegranates returned to market booths

But your face, my boy, remains changed.

I had a boy in love, I had a boy,

Clear was his voice, clear were his eyes

The battle now silent, he returns to the gate

But his gait is heavy, and his face sealed.

הייתי נער

היעדים מטוהרים והרוסים

שלגים על החרמון מול שמש נמסים

ובעיירת רפאים על הרמה

חמור בודד תועה כבטרם מלחמה

הקיץ שב למשלטיו הישנים

אבל פניך נערי נותרו שונים

הוילונות הוסרו והנייר גורד

פקיד העירייה נעל את המקלט

שלוחות הדשא מטפסות ומעלות

ירוק טרי על צלקות התעלות

הרימונים חזרו לשוק לדוכנים

אבל פניך נערי נותרו שונים

היה לי נער מאוהב היה לי נער

צלול היה קולו צלולות היו עיניו

הקרב נדם ושוב קרב הוא אל השער

אך הילוכו כבד וחתומות פניו

Life resumes

Snow melts on Mount Hermon,

cleansed by the golden sun

But the boy’s face has changed

Is covered with worry, twisted, shriveled

a mirror reflecting the horrors of war

The battle has ended in the desert

But has just begun in the boy’s mind

A lifetime of suffering

An innocent, lost

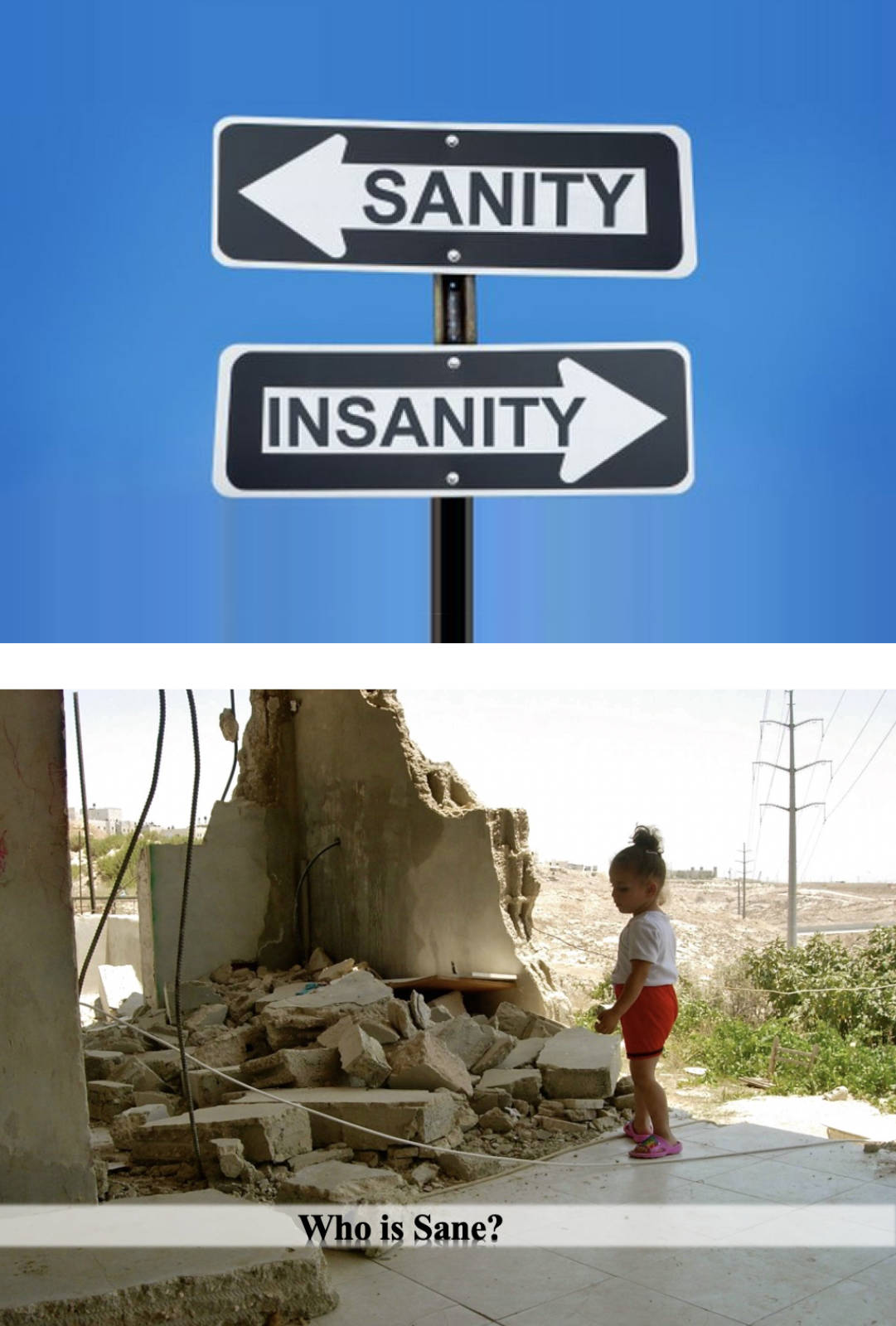

Occupation of West Bank & Gaza: Being Sane in an Insane Place

Thinking back to my early years, I can see that encounters with death during my military service, testing boundaries, questioning commonly held beliefs, seeking the truth, questioning authority, and searching for ways to choose between intuition and logic were all inherent parts of who I was. I loved to learn by examining what I or others thought was right or wrong. I did not do it alone; for example, there was an incident where some soldiers did not come back from an R&R furlough to the base in the Gaza Strip, but instead admitted themselves to a mental institution [to avoid returning to the base in Gaza]. This meant that I could not give a much needed break to other soldiers in our unit and I was furious. I expressed my outrage to my mother on the phone. In a soft voice, my mother responded to my anger by saying, “Perhaps those who admitted themselves to the mental institution rather than coming back to the camp were the sane ones”. I was speechless. In that one, short sentence, she forced me to question the whole notion and definition of sanity. In my own way, I continue this path.

Outraged at the offense of others

Who hid, feigning insanity

Angry at them for their callousness

And lack of service

They refused to fight

their defiance saved themselves

from the real insanity of war

Rehab.: Kicking my Surgeon’s Butt with My Calf-Less Leg

As part of my rehabilitation from the 1973 war injury, I remember the oddest scene in the hospital where I rudely and highly inappropriately confronted my young surgeon in the hallway in front of other wounded soldiers telling him something to the effect that, “You told my parents that you hope I will be able to walk well one day. It won’t be long before I walk normally and kick you with my calfless leg.” Without hesitation, the doctor slightly rattled one of my crutches, which caused me to lose my balance and fall to the floor, humiliated, in front of my fellow hospitalized soldiers. The doctor then said to me something like, “If you can walk so well, why don’t you walk without crutches right now.” Oddly enough, this proved to be a ‘magical and highly effective dose of medicine,’ and at that very moment, I knew I would fully recover, which indeed I did. Within a year of my injury I played college ball on the basketball team of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and years later I make a career of deep see diver, climbed Kilimanjaro, played competitive Ball to age 55yo, drove motorcycles in the Himalayas and much much more.

My dose of medicine

A rattling of crutches done by my surgeon

An elixir, the motivation I needed

To walk, to heal from a devastating injury

To push my body past the limits of what I thought possible

Idiotic Myth: “Israeli Paratroopers Don’t Get PTSD”

Right after this bizarre scene with my doctor, I started training myself to walk again. I rejected any physical therapy and spent long nights, all alone, walking on the hospital room porch, holding on to the rail, and ‘silently’ crying in pain. When I eventually went back to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem to continue my studies, I also went back to riding my motorcycle and playing basketball on the university team. The subsequent surgeon, unusually but effectively, used my performance on the basketball court as a yardstick to measure when I was ready for the next surgery. Obviously, this injury was followed by a few years of intense pain, determination, surgeries, rehab, deep contemplation, and finally, full recovery in spite of a very poor prognosis. It took me many years to attend to the traumatic aspect of the war injury & war experience and numerous other traumas I’d experienced in my lifetime and embrace the illuminating concept of Post Traumatic Growth (PTG) rather than Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Learning to walk again

alone At night

the only sound, My heartbeat

feeling intense waves of pain

Looking for an oasis of healing

A spring inside of myself

A determination to heal, spiritually,

Physically and emotionally.

“All of you guys are missing some parts!”

Two young ones, not quite adults, still nourished by the springtime of possibilities. We held hands and while walking the coast-line of the Red-Sea, immersed in the calm beauty of the sunset, enjoyed the silence of getting to know each other. She was a 19 year old young Israeli woman. I was a few years older and we had just met. We touched each other softly with a sense of innocence and wonder, more exploratory and curious than sexual. We sat with legs crossed, her head on my shoulder, as we watched the slow decent of the sun. Her soft fingertip touch came to the place where my calf was blown off in the war. She briefly paused and broke the silence by casually offering up: “All of you guys are missing some parts, aren’t you?” Then, she continued to silently and gently stroke my leg. She said it as a simple matter of fact. She could equally have said “The ocean temperature is moderate.” It was a powerful, insightful and profoundly sad moment for me. While, like most of my fellow soldiers, I was still in denial of the profound traumatic impact of my battle experience and war injury on me, it was painfully clear to me that this young woman was already completely resigned and profoundly aware of the, so called “parts” that so many of us, young men – soldiers, “were missing”.

“Missing some parts”

Parts suddenly removed

Limbs blown off

Our souls not quite intact,

Grappling with a broken body

From the injuries of yet, another war

Re-Living my 1973 War experience on Memorial Day in 2022

Visiting Israel during memorial-day for the fallen soldiers has added an interesting and intense aspect of the visit. I joined my best friend Eitan to his military units annual memorial-day ceremony at Tel-Saki on the Golan Hight where his small unit was surprised attacked in the 1973 war and found itself surrounded by hundreds of Syrian’s tanks and soldiers. The ritual included the parents and siblings and the photos of the soldiers who died right there. Some members of the unit, got severely injured and 50+ years later are still heavily disabled. I chose to walk into one of the dark underground tunnels in Tel-Saki in an attempt to remember and re-live my battle experience in the 73 war in the Egyptian front across the Suez Canal. As expected, walking into the dark, long and narrow tunnel, I encountered strong bodily memories of tunnel fighting, of keeping the non-stop the intense fire upfront/ahead while stepping on enemy soldiers’ dead bodies. It was, definitely, an intense experience, but fortunately did not activated any of my PTSD, on which I ‘worked’ for many years, after I finally realizes the stupidity of the belief I was indoctrinated with, that “Israeli paratroopers do not get PTSD”.

Theme #2: Military Experience

Theme #3: My Family & My Health

Theme #4: Questioning Authority, Challenging Accepted Truths & Debunking Myths

Theme #5: Psychology of war – The Love of Hating

Theme #6: Adventures & World Wide Travel

Theme #7: On Good Rules & Bad Rules: Pushing the Limits & Freedom Seeking

Theme #8: My Moral Junctions

Theme #9: Looking at Death Straight in the Eyes

Theme #10: Professional Psychology, Zur Institute & Professional Achievements

Theme #11: On Men, Women, Gender Role and Gender Relationships

Theme #12: At 70’s: Next Mountains to Scale

Before exploring ‘life after leaving,’ I want to revisit my time in Israel in the early 70s as an officer in the Israeli army. Our highly trained unit was stationed in a tremendously overcrowded, poverty-stricken, and polluted refugee camp in the occupied Gaza Strip. The camp consisted of thousands of single-story houses jammed full with multiple generations in families, and often chickens and ducks as well! The narrow streets—actually muddy alleyways—emitted the foul stink of urine and excrement from donkeys, mules, chickens, ducks and… humans.

Before exploring ‘life after leaving,’ I want to revisit my time in Israel in the early 70s as an officer in the Israeli army. Our highly trained unit was stationed in a tremendously overcrowded, poverty-stricken, and polluted refugee camp in the occupied Gaza Strip. The camp consisted of thousands of single-story houses jammed full with multiple generations in families, and often chickens and ducks as well! The narrow streets—actually muddy alleyways—emitted the foul stink of urine and excrement from donkeys, mules, chickens, ducks and… humans. I despised myself for not protecting this woman and her children, for not standing in front of the Israeli bulldozer the way the heroic ‘Tank-Man’ stood in front of the tanks in Tianaman square in China.

I despised myself for not protecting this woman and her children, for not standing in front of the Israeli bulldozer the way the heroic ‘Tank-Man’ stood in front of the tanks in Tianaman square in China.