Encounter with Phosphorous Grenade at Age 10

At age 10, during a Purim holiday celebration (similar to Mardi Gras) where thousands of Israelis gathered in the center of Tel-Aviv to celebrate, an Israeli soldier mistakenly launched a phosphorous grenade into the crowd while intending to throw a colorful and harmless smoke grenade. The burning phosphorous struck both my legs and my hair, turning me into living torch. Due to the nature of phosphorous, which sticks to the skin and can burn without oxygen, it was hard to put the fire out and I ended up with third degree burns on my legs and a scar on my hairline and spent a month in the hospital. (For the rest of my life I could always resonate with the famous Vietnamese Napalm-Girl, who was photographed in 1972 screaming in torturous pain, after U.S. air-force reprehensibly, inhumanly and immorally dropped napalm on her village.) Oddly enough, my most vivid memories of this ordeal were having fun in the hospital riding a wheelchair on two wheels and spending time with my mother who had also received burns from the same grenade and was in the next hospital room.

I had been set on fire

A young child burned by a phosphorus grenade

The mood, a juxtaposition of celebration and terror

My heart choked by fear

Burns covered my body

Purple scars covered my skin

remnants of a painful memory

I became stronger from this surreal experience

more resilient and less fearful

Looking at Death Straight in the Eyes: An Encounter w/ Death

Soon after, as a lieutenant and combat officer, just 19 years old, viewing life as a prism of possibilities, I found myself at the greatest boundary of all, that of life and death. For the first time, I held a soldier’s dead body in my arms. Simplicity and innocence vanished and once again a new perspective opened before me, a new consciousness. I felt so profoundly the preciousness, the fragility of life and the importance of living each day fully, with care and integrity, as if it were my last day on earth. To this day, I try to live that way.

Life with its infinite possibilities

Could vanish without warning

Cradling a soldier’s dead body in my arms

Mourning a life taken too soon

A new perspective formed in my consciousness

An appreciation for each day

As it could be my last

Shooting the Light Bulb – How Dumb is That?

While some boundaries are physical, existential, or spiritual, others are developmental, metaphorical, or metaphysical. I remember a time, during my military service, when three of us, all officers, were housed in a cement bunker. Late one night, we were all very tired and had turned in for a good night’s sleep. I was already in bed and, instead of doing the obvious of getting up and turning off the light switch, I reached for my handgun and shot out the single light bulb hanging from the ceiling. While I accurately hit the bulb, which effectively turned the light off, the bullet ricocheted wildly around the cement walls for what seemed like a very long time, seriously endangered the life of all three of us. On my list of boundaries, this would easily rank as a highly reckless, stupid, and an utterly irresponsible way of pushing boundaries – and fate.

The bullet ricocheted throughout the room,

after initially piercing the air,

and making the room change from light to dark

In the moment, the only murmur was my heart

Which grew louder, telltale heart, like from Poe,

I had risked their, our… lives

Thumbing My Nose at Death on a Bridge of Fire

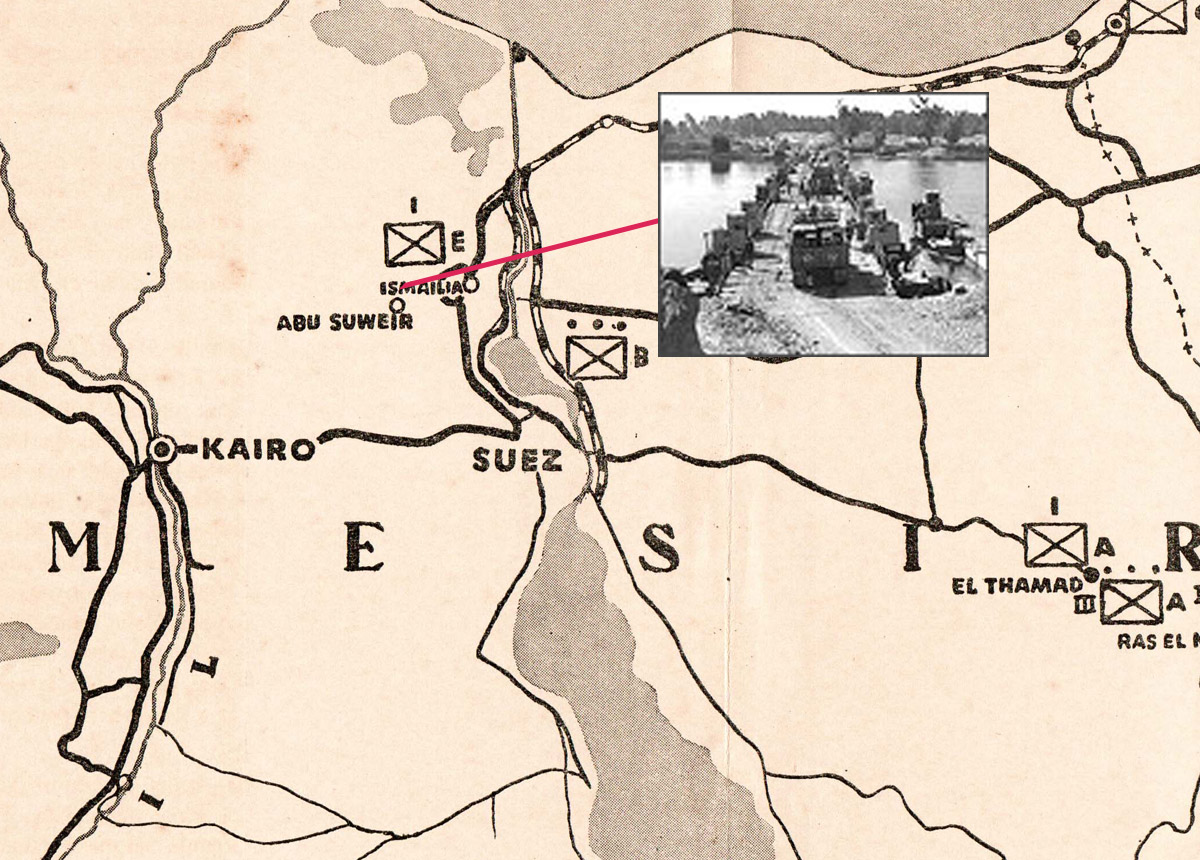

Towards the end of the 1973 war, my unit was finally deployed. We were assigned to cross a bridge across the Suez Canal and head north towards the revered city of Ismailia. At this point of the war the Egyptian army was highly concerned that if the Israeli Armed Forces crossed the Suez Canal, they would subsequently have a clear path to Egypt’s capital, Cairo. As a result, the Egyptian army was defending the bridge that my unit had been assigned to with all their remaining military might, relying on intense artillery bombardments, air force bombings, and anti-tank guided missiles to deter the incoming Israeli army. When we arrived, Israeli tanks, personal carriers and jeeps were on fire and literally flying off the bridge. It was an intense game of chicken between the Egyptian bombings and the Israeli military engineering unit, which was rapidly rebuilding and repairing the repeatedly hit and damaged bridge. Amazingly they were able to keep rebuilding despite the catastrophic losses they were suffering.

Then, I received my orders: we were commanded to cross this fiery strip and move deeper into Egypt. While the rest of my unit quickly jumped into vehicles and sped as fast as they could into the clouds of smoke that covered the bridge, my recklessness, bravery and perhaps my stupidity spurred my buddy and me to cross this death zone by foot. As fire and metal rained down around our unprotected bodies, we sarcastically argued over who would be the first to die, and who would get to put a wreath on the grave of the other at the prestigious famed national military cemetery on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem. Halfway across the bridge I suddenly felt compelled to stop. A strange sense of calm and quiet came over me despite the deafening bombs and missiles exploding all around. Almost engulfed by the chaos and destruction, I looked up at the sky and extended a defiant middle finger to God, a gesture by which I was telling Death, “I do not fear you!”

This attitude of fearlessness towards death, which has harmoniously and consistently coexisted with my deep reverence for life, has revealed itself in multiple ways throughout my life, such as in my predilection for evacuating hospitals against medical advice, diving the magical but lethal Blue Hole, shooting the light bulb, challenge-riding a motorcycle at the Himalayas by 4,000ft drops and many other death-defying ventures. My mother vowed she wanted to ‘die erect,’ so perhaps there’s a strain of this mentality I inherited from her!

Even as I walk, surrounded by flames

On this Bridge of Fire

You, death, will not win!

Though you may try to burn my aching body

You will never singe my soul – my essence

Oh death, You will not defeat me!

Monkey & Me: Respect For & Identification With the Enemy

After a few days of cautiously moving towards enemy lines in the 1973 war, our military unit became the target of artillery shells. Some fell to the left of us, some to the right, some in front of us where we were headed, and some behind us, where we had been an hour ago. In a curious, fascinating, and yet terrifying pattern, the shells began to gradually close in on us in a perfect lethal circle, closer and closer on all sides. As our unit paused under a grove of high palm trees, the shells began falling so close to our group that it became obvious that the artillery weapons were being systematically directed by someone or something that was aware of our location. Was there an unseen aircraft tracking us, a satellite, or an eye in the sky?

As we frantically tried to figure out who/what was doing this we peered at the sky through the fronds of the palm trees above and suddenly spotted what in some military jargon is called a “monkey” — a perfectly camouflaged Egyptian soldier sitting atop one of the trees, trying to blend in with the thick canopy. We instantly realized that he was the one providing his fellow artillery soldiers miles away with the exact location of our unit. Within a milli-second, about 20 to 30 solders aimed and rapidly shot their M-16’s automatic guns at him. By the time he hit the ground he had several hundred bullet holes in him. Needless to say, he did not suffer much. A couple of distressed, frightened and enraged soldiers even shot a few more rounds into the lifeless bleeding body.

I looked at this bullet-ridden corpse and experienced an upwelling of admiration, respect, and even awe, for this man who had directed his artillery on our unit… and in the end, on himself. I considered how he had been deliberately and consciously ready to face death in defense of his country, just as I had been a couple of days prior while crossing the bridge of fire. My feelings of identification and admiration were not shared by my fellow soldiers. In fact, a fellow officer rushed toward the body and took the bayonet off his gun, both as memorabilia and as an attempt to humiliate the enemy. I was unexpectedly overcome with rage and hatred towards this man’s lack of acknowledgement of the bravery of the monkey. I instinctively wanted to protect his body, and at the bare minimum, have our unit spend a few seconds around it to honor the complex relationship that we had with our enemy. I did feel hatred towards the threat he had posed to myself and my soldiers, yet I also was touched by his sacrifice and courage. I was very aware that I could have been the one to be riddled with bullets just a couple of days earlier on the bridge.

In effect, this is what we soldiers are about: walking the tightrope of potential sacrifice while defending our country as heroes. Yet, I suspected that the monkey, like me, had not viewed his defiance of death and willingness to sacrifice as particularly brave or heroic. Rather, his act was a way to embrace life in its fullest. Ironically, saying ‘Yes to life’ meant also saying ‘Yes to death.’

I identified and could understand

the role of the monkey

a soldier who provided his artillery soldiers

with the location of our unit

That he had been willing to die

and willingly sacrificed himself,

without fanfare,

as part of the greater ecosystem of life

and for his country.

This Moment Could be My Last

We survived, at least physically, the crossing of the bridge over the Suez Canal under rain of fire in the 1973 (Yom Kippur) war and the close call with the monkey aiming the artillery on us. Getting closer to our target city of Ismailia, my buddy and I were driving a jeep on a mission in coordination with a sister unit when we lost our bearings and shockingly found ourselves behind enemy lines. There, suddenly and unexpectedly we arrived at a most horrific, eerie sight. In front of us were the widely scattered remains of an Israeli army jeep which had literary evaporated, annihilated into thin air when struck by a lethal Egyptian anti-tank missile. We also stumbled upon the tiny dog-tag, all that was left from an Israeli soldier whose body, like most of the parts of the jeep, had vanished into the same thin air.

Realizing that the jeep we were driving was situated exactly where the evaporated jeep once stood was a surreal experience. We knew that in no time, at any given moment and without warning, we too could vanish and annihilated just like the passengers of the other jeep. We exchanged looks of awe mixed with wonder and horror. As we silently and with full presence inched our way back to our unit, we struggled to metabolize the very real possibility of our instantaneous annihilation and death. Thinking of being evaporated in an instant felt very different than considering dying by a bullet. This really drove home how we had neither control of our destiny nor predictive power as to what might be awaiting us. I truly got it how life, and its continuance, is such a mystery, and ultimately, such a gift.

The scattered remains of an Israeli army jeep

A single dog tag

all that was left of a fellow soldier

In an instant death

could tap her cold, bony fingers

Against our shoulders

And in that unreal moment

Life suddenly became more sacred

When my Calf was Blown Off in Battle of Ismailia: Am I a War Hero or My Parents’ Sacrificial Lamb?

In the waning minutes of the Yom Kippur (1973) war, I once again found myself at the aweinspiring boundary between life and death during the Battle of Ismailia when I was seriously wounded after most of my left calf was blown off and I collapsed in complete and utter silence. The silence, as I put together months later, was partly due to the fact that I lost my hearing when the intense enemy bombing ruptured my eardrums. As soon as I collapsed into this zone of silence and injury, as if someone had literally pulled the rug from underneath me, I told myself, “I lost my leg because I should have not gone (or walked) to a war that I did not fully believe in.” (Later in life I followed up on this interpretation and explore in depth the constructs of the ‘metaphor of illness’ or the meaning of dis-eases.)

I was evacuated under heavy fire, and to my deep distress found myself in an armed vehicle, which I knew to be an easy target for the enemy’s lethal shoulder missiles. What was strange about the morphine-induced delirium I experienced during this evacuation was that I became less worried about being blown up by a lethal Egyptian shoulder missile than I was about being part of an imaginary ‘cosmic play,’ in which I was the sacrificial lamb to my peace-loving parents who were simultaneously and paradoxically against the war while proud of their ‘sacrificial hero/wounded lieutenant son.’ Years later, in an attempt to make sense of this bizarre but intriguing experience, I devoted considerable time to exploration of what is known as the Medea Complex, or the unconscious wishes of parents to kill their children as manifested by the 25 years (one generation) average of war cycles in modern times.

War hero, sacrificial lamb

In a war I did not fully believe in

My left calf, blown apart

Like the peaceful beliefs that had been planted,

like tulips in my heart

The world around me, sounds, colors

Faded in, briefly

My life, my being, my very essence

My fate, left in the balance

Between the desert and the cosmos

The Crater Dilemma: Instinct vs. rational & impulse vs. logics

Another memory from the 1973 Yom Kippur war: we are deep in the desert and artillery shells, with their lethal downpour, were raining down all around us. Each exploding shell created a crater in the sand. I was standing at the edge of one of these craters, covered with dust from the latest explosion. Obviously, my instinct told me to run for my life, to run as fast as I could away from that crater before the next shell struck, but my military training repeatedly ran through my head telling me that ‘two bombs never fall in the same place.’

Accepting that premise meant that this new crater was the safest place around and therefore I should jump into it, against all my instinct. In the confusion of life and death, it was the fight between intuition and the brain – instinct vs. rationality. I jumped into the crater, which probably saved my life. I have, since that day, always wondered how many times in life we stand at the edge of craters needing to weigh our instinct against our rational inclination; our impulse against the logical choice. Indeed, life presents us with situations where a crater may even sink us into the earth, but where the seeds of creativity may flourish. (Listen to an audio recording, describing this junction)

A recollection of the 1973 Yom Kippur war,

shells exploding,

undisturbed sand became a bed of craters,

for us soldiers to hide in perhaps,

from the storm of shells that poured fire on us

even impulsivity had reason over logic,

meant life and not a sudden death

Diving the ‘Diver Cemetery’ – The ‘Blue Hole’ 184ft (!) at Dahab

As part of me being an oceanographer, I was also a deep-sea diver where I regularly dove the spectacular coral reef in the warm and clear waters (up to 300 feet visibility) amid brilliantly colored fish, turtles and eels. I also dove with sharks in Ras Muhammad off the tip of Sinai next to beautiful and rarely visited or touched coral reef. But most thrilling and risky was adventure-diving (with the standard of air mixture of 21% oxygen, 78% nitrogen) the Blue Hole, also known as “The World’s Most Dangerous Dive Site” with the nickname “Diver’s Cemetery” with a depth of over 200 feet (60 meter)! It is estimated that it claimed the lives of 130 to 200 divers in recent years, primarily due to Nitrogen Narcosis.

Diving with sharks in Ras Muhammad

off the tip of Sinai

next to beautiful and rarely visited or touched coral reefs,

an exhilarating blend of risk

And reward

Pleasure and pain

Life, and the very real possibility of death

Driving Safaris in the Serengeti in East Africa

In addition to my scientific activities (age 26-27), I also drove safaris in Kenya and Tanzania across the vast savannahs and landscapes of the Serengeti, Ngorongoro Crater, Lake Nakuru, and Lake Turkana. The parade of life and the seemingly endless herds of lions, giraffes, zebras, elephants, wildebeests, rhinos, hippos, crocodiles, and buffalos were everywhere. To this day, I vividly remember the hundreds of seasonally migrating zebras and wildebeests that did not make it to the next watering hole. This significantly influenced me and much of my psychology work as I thought of the interconnectedness of life and death and how often thoughts of mortality unconsciously influence our actions and thoughts.

In Africa

Rhinos, crocodiles and elephants

A collection of animals roaming scattered terrain

The connection between all creatures

Great and small

Interconnectedness

Like animals,

Humans were bound together

Swept up in life,

ashes scattered in death

All things tied together.

Cultures’ attitudes towards life, death, destiny & community

I learned a great deal about different attitudes towards life and death during the time I spent in remote areas of the Somali desert. I watched in bewilderment as tribesmen let their only source of water in that desert area be polluted with a seeming disregard for their own lives or the consequences: the inevitable, rapid destruction of the community. These new realizations regarding different cultures’ varying attitudes towards life, death, destiny, community, responsibility, survival, and spirituality initially baffled, confused and, at times, upset and depressed me. Later on, they humbled me and irreversibly impacted me for the rest of my life. I have learned not to assume anything about other cultures and to always stay anthropologically open, deeply respectful and able to honor and approach cultural diversity with a sense of awe.

A community, enriched or

Destroyed with thoughts of others

Or maybe not at all…

A polluted well suddenly waterless,

not potable, incapable of sustaining life

Survival for a community

destroyed instantly thrown into the wind

These occurrences changed my

View of humankind and its

Responsibility to others

Made me cynical, despondent

Contracting Severe Malaria in the Most “Ideal” Place

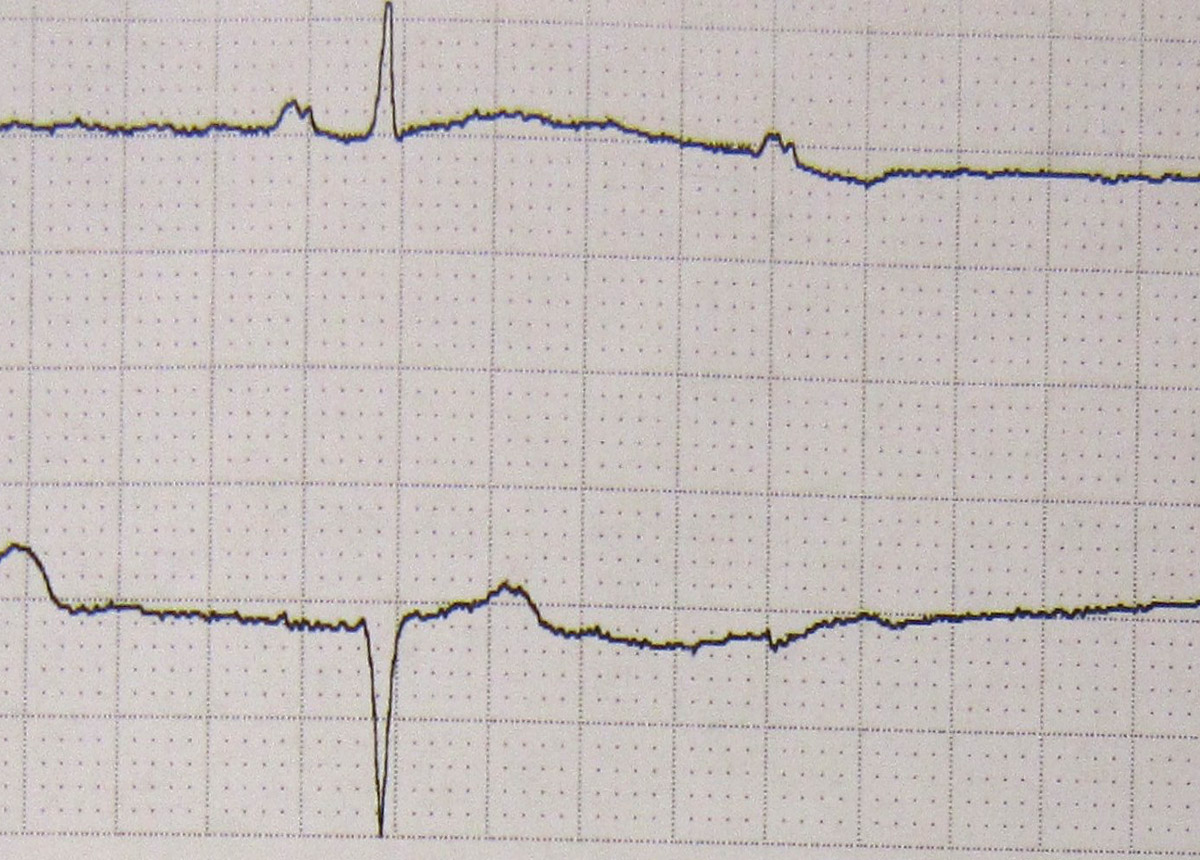

I was around 27 years old traveling in East Africa, hiking, climbing mountains, scaling rocks, riding small motorcycles (pikipiki), studying fish-ponds, driving safaris, canoeing on the Indian Ocean and Lake Victoria and ‘socializing’ with crocodiles in Lake Turkana. I found out that, apparently, the anti-malarial Chloroquine pills that I had been taking were no defense to the disease carrying mosquitoes I encountered after crossing the border into Tanzania, as I ended up coming down with a serious case of malaria. It was fortunate as I got the illness while visiting a friend who happened to be researching malaria at none other than the East Africa Institute for Tropical Diseases. I was fantastically cared for medically and felt super safe as I was seen by several highly experienced doctors and researchers who were top experts in the treatment and study of malaria. There was a surreal atmosphere as they had seen thousands of cases like mine over the years and could predict to the second when the high fever (107°F) ![]() would turn to chilling cold

would turn to chilling cold ![]() and visa versa. After a couple of weeks of intense sickness, I recovered enough to where I could continue to travel throughout East Africa. It took me many months to gain my full vision and strength.

and visa versa. After a couple of weeks of intense sickness, I recovered enough to where I could continue to travel throughout East Africa. It took me many months to gain my full vision and strength.

Sick with malaria in Tanzia,

the world had turned from scientific observations

to an atmosphere of terror,

where I became a petri dish of disease,

until I recovered slowly, painstakingly slowly —

sick in Africa was an experience I’d never forget.

Being Hysterically Blind in the Face of Torture

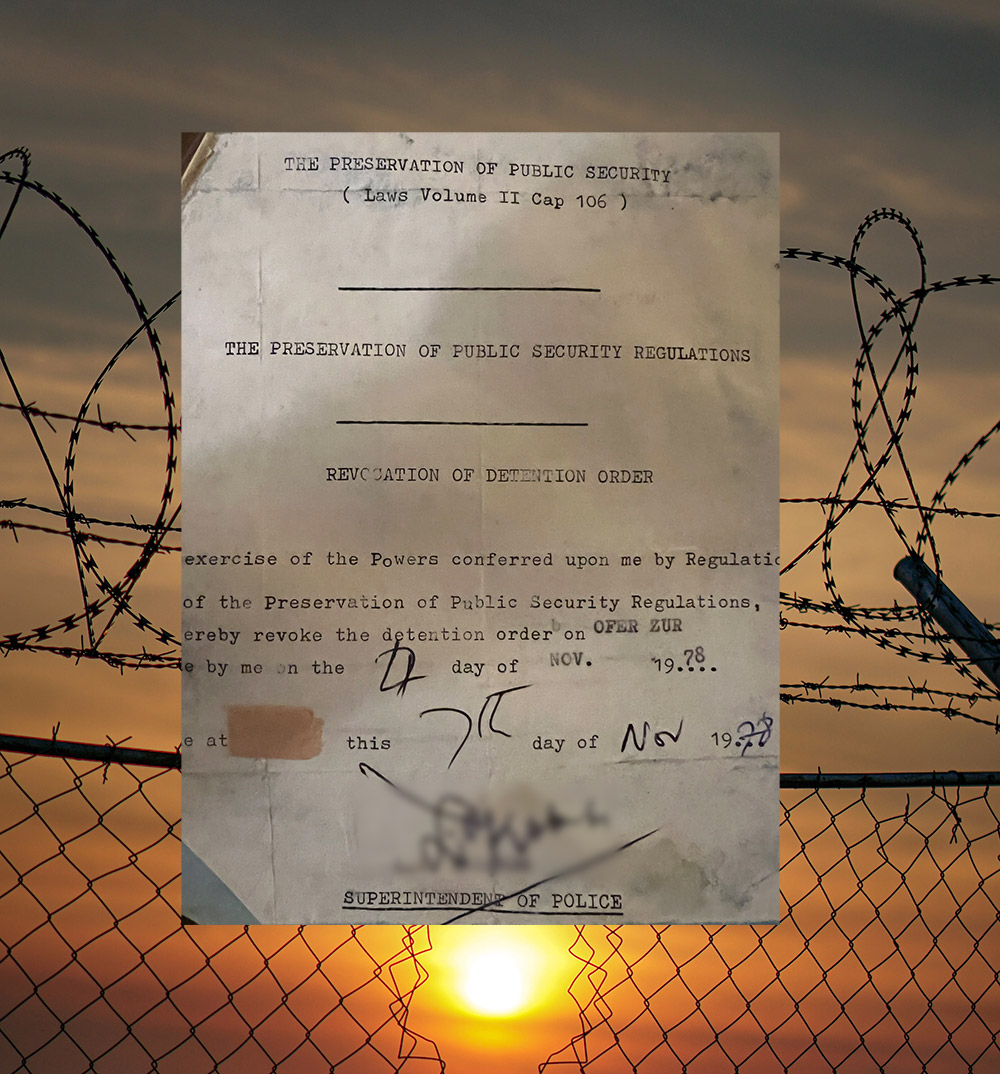

Going too far in the right direction was not new to me. Through many years of traveling in Africa I was drawn to visit a fascinating and unique ruined old spiritual center in a country in Africa where I was clearly unwelcomed. Needless to say I was drawn to this destination, or better said driven and compelled to get there. This drive was definitely not new, it drove me throughout my life to ignore obvious obstacles, to dismiss basic rules, and deny extreme dangers.

This includes an incident some years ago in which I chose to turn out the light in a crowded bunker by shooting the lightbulb out or stood still and refused to run on the heavily bombed bridge or many other similar acts of looking at death straight in the eyes.

Perhaps the most terrifying was the expected of being arrested and detained on some unclear grounds in a foreign land with no language or knowledge of the culture or the terrain. My passport, at that time was definitely not helpful, and probably put me at high risk. I was detained in a remote prison, not knowing the language, left to wander around only wearing underwear, with hundreds of men around me but with no common language or familiar culture. At night I was housed in a 6ft x 6ft cement cell, sitting on the floor with my back to the walls with three more prisoners with no way to comment, hearing the horrible, extremely loud, painful screams of tortured prisoners in the next building neither facilitated a restful night sleep nor peace of mind.

Detained, alone, afraid

On lands that were not my own

My face covered in shadows

In a remote prison

Screams punctuated the heavy air

Beads of sweat clung to my body like tears

Suddenly I became hysterically blind

thinking of my own pending torture

covering my mind In cobwebs of horror

My captors shining a light on me

My release from captivity a blur of emotions

A soul full of sorrow – A shadow inside my eye,

To remind me of my ordeal.

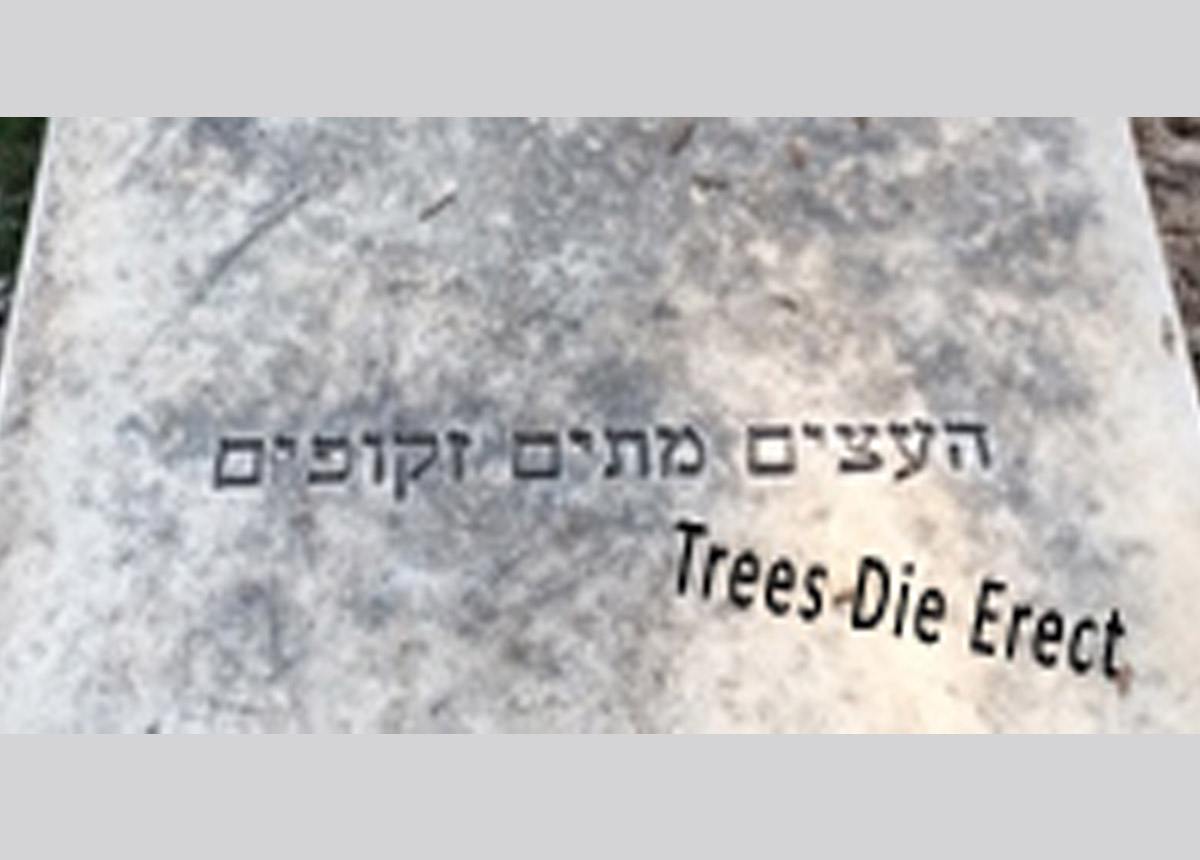

“Trees Die Erect” – Mother Parted Exactly as She Planned

I continued my work, exploring the roots of war and promoting peace, which led me to literature that discussed the meaning of the fact that the average frequency of war is 25 years, which corresponds to the span of a generation. The theory posited the puzzling and odd idea that war may be the unconscious wish and impulse of parents to kill their children, or what is also known as the Medea Complex. I asked my mother her thoughts on this idea and did not hear back from her for a couple of months. Then one day, I got a package from her with probably all the available literature on this obscure topic. She noted that compiling this literature was one of the most difficult challenges she had ever faced. That was the last correspondence I had from her as she died soon after from her second heart attack in November 1982 at age 68. Mother repeatedly told us that she neither wanted to slow down in old age nor have a prolonged death. So on her gravestone we engraved her own words -“Trees Die Erect”.

One never to slow down

An intellectual giant

A loving mother

A questioning soul

Who didn’t wish to linger too long between life and death,

between sunshine and shade

So on her gravestone we wrote the words

“Trees Die Erect”

Flatlined for 90 Seconds – Disappointedly Did NOT See God

In the millenial year of 2000, I suffered my first heart attack and cardiac arrest at the age of 50 (100% occlusions of LCA) and crossed the boundary of life and death (flatlined) for 90+ seconds. I remain disappointed that I neither saw a white light nor God, a truly wasted opportunity. With a stent in place, I have increased my focus on my “bucket list”. In that same year, my father died, but unlike my mother, he went slowly at the ripe old age of 84.

In an instant of course

Life can change,

Sands stop running through

An hourglass, my hourglass

My life suspended

Each day meant more than the day before

A new journey

A thirst for adventure

A new appreciation

A life reborn, made anew.

Buying into my own Bullshit about “A Glamorous Place to Die”

As Eitan and I were training for the Kilimanjaro climb, many friends and acquaintances confronted me. They wanted to know why at the age of 57, after having suffered a major cardiac arrest, I was so keen on risking my life with this climb of Mt. Kilimanjaro alongside my 14-year-old son. After growing tired of the questioning, and what felt like narrow-mindedness, lack of imagination, and subtle guilt-inducing harassment, I started responding with, “You are absolutely right. I may die on the mountain! However, can you think of a better place to die than on top of the highest, most gorgeous, stand-alone mountain in the world?”

When people continued to challenge me about having my 14-year-old son with me on this venture, supposedly risking my life, I came up with this response, which I told the ‘concerned/questioning ones’: “If I am to ‘glamorously’ die on top of spectacular Kilimanjaro, I will be cremated there, and my ashes will be placed in a Tanzanian ebony box. Eitan will bring me down the mountain and back home in this beautiful small carved memento.” This ebony box story was repeated whenever I was confronted or accused of being irresponsible by friends, colleagues, and guest at dinner tables. While Eitan did not seem to be flabbergasted, distressed or upset by this story, many other people did.

The final twist to this story came at 18,000 feet, where I became disoriented and suddenly unable to breath and experiencing severe heart pains. This was a clear sign of (another) potential heart failure. Instead of asking Eitan who, according to plan had carried my nitro (Nitroglycerin), to stay nearby and be ready to hand it to me, I found myself believing my absurd story and (yes, sincerely) telling myself “There is no better place to die…” Miraculously, I survived, in spite of myself.

There is no better place to die

But why

Not enjoy the scenery

And the bond with my son

As long as I’m not done

Living

Riding Motorcycles at the Himalayas at 18,380ft

In August 2012 my son, Eitan (19), and I (62) went to the highest ‘ridable’ road on earth at 18,380 feet above sea level – in the Himalayas on … motorcycles. The two-week adventure turned out to be one of the most physically and mentally onerous experiences of my life. Driving the narrow, rocky roads often bordered by cliffs falling thousands of feet (with no guard rails), blind corners, reckless, over-loaded trucks, long days of riding through endless potholes, and water crossings turned out to be an unparalleled adventure and realization of a dream.

18,380 feet above sea level

My son and I

zigzag, cut through

Earth and heaven,

Feel sun and shade at our backs

As we ride

The Ultimate Challenge-Riding a Motorcycle by 4,000ft Drops

The enormity and grandeur of the Himalayas are incomparable and so are the centuries-old sacred Buddhist temples and monasteries we visited. Sometimes it felt like we were riding the clouds. The trip evoked in me such humility and helped me come to terms with physical and age-related limitations (age 62). Ultimately, once again, we looked death straight in the eyes (or at least around every blind corner). And, of course, it also intensified a special connection with my son. In contrast to my experience, Eitan found the trip joyous and quite easy.

I rode clouds with you

On soil as old as time

As sacred as your joy

My heart humbles

As I look death in the eye

With you by my side

Dying Well: Forethought, Consciousness, Planning, Joy & More

Alongside the question of ‘what is next in my life?’, I ponder ‘how do I want to die?’. I know that I neither want to die ‘erect’ (i.e. in my prime) as my mother did, nor do I wish to go through the lengthy, painfully slow journey that my father took in the final period of his life. My young son, Ilan, insightfully said one day “Aba (dad), you will not die on top of Kilimanjaro nor on the glacier in Alaska nor among the sharks in the deep ocean. You are mostly likely to die slipping on a banana in the local Safeway.” When it comes to death, I love the scene of Little Big Man where Chief Dan George announces “Today is a good day to die” and wanders off into the woods. The “Right to Die” law that was passed in California in 2016 gives me some choices or control regarding the way I may choose to die, which is a relief. I found appealing the story of a terminally ill California woman who invited friends from all over the country to a ‘farewell party’ – a jubilant celebration of her life and relationships. After two days of partying she retired to a room where, with her doctor and a few close people, she took the drugs that ended her life. Personally, I also wish to die among my family and friends but I am also resign to not knowing how I will spend the last days or last minutes of my life.

This day could be my final one

A foot placed between sky and sand

Heaven and earth

Life and the in-between

And the precious moments

Sun fading to pink

Tender embraces of family

Long walks with friends

Plane rides above the earth

To faraway places

A slower pace

An embrace of all that is.

Re-Living my 1973 War experience on Memorial Day in 2022

Visiting Israel during memorial-day for the fallen soldiers has added an interesting and intense aspect of the visit. I joined my best friend Eitan to his military units annual memorial-day ceremony at Tel-Saki on the Golan Hight where his small unit was surprised attacked in the 1973 war and found itself surrounded by hundreds of Syrian’s tanks and soldiers. The ritual included the parents and siblings and the photos of the soldiers who died right there. Some members of the unit, got severely injured and 50+ years later are still heavily disabled. I chose to walk into one of the dark underground tunnels in Tel-Saki in an attempt to remember and re-live my battle experience in the 73 war in the Egyptian front across the Suez Canal. As expected, walking into the dark, long and narrow tunnel, I encountered strong bodily memories of tunnel fighting, of keeping the non-stop the intense fire upfront/ahead while stepping on enemy soldiers’ dead bodies. It was, definitely, an intense experience, but fortunately did not activated any of my PTSD, on which I ‘worked’ for many years, after I finally realizes the stupidity of the belief I was indoctrinated with, that “Israeli paratroopers do not get PTSD”.

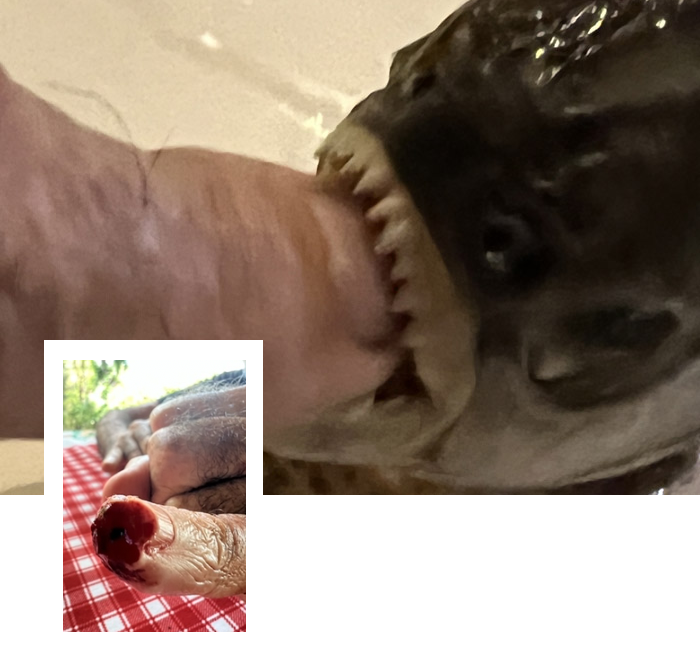

Challenging Encounter with Fear, Mastery and . . . PIRANHAS on the Amazon River

In 2022 at 72 years old, I have decided to confront fear, challenge, and adventure by going to Brazil and spend time in gorgeous, adventurous Rio de Janeiro, on the magnificent enormous Amazon River and encounter unique personal challenge with the legendary dangerous awesome Piranhas.

I travelled in this 3 weeks adventure with my beloved nephew, Tal (52) and a young friend Jenn Gaskell (32) a Scottish doctorate-mathematician, and ultra marathon runner.

One more frontier

To travel to

To face fear

To experience pain

As gateway to eternity

A short video of our delightful time in Rio, Santarem and the gorgeous Amazon

Rio

The city that never sleeps

Majestic, draped in a rainbow of colors

The heartbeat of life

The soul of Brazil

A short video and 6 slides of my amazing encounter with the awesome piranhas and the rational for this rather ‘crazy adventure’

Piranha’s song for my 73rd birthday

Piranha

Our first encounter

Your sharp famous teeth

a reminder of your legendary power

My eagerness to engage

Growing Old, Facing Death, Walking on the Ice…

Towards the end of 2022 at 72 years old, I developed several undiagnosed mystery medical complexities, such as walking pneumonia and an enlarged heart. That have slowed me down physically and emotionally, luckily, not spiritually or intellectually. It brought up, again, the question of when is the right time to walk on the ice or the time for the (polar) bears to eat me (so the young ones can hunt, eat the bear, survive & live longer).

Having the warm-loving-immense support of Jenji, my kids and my nephew, Tal, has meant the world to me. Additionally, being part of community, such as weekly ‘Walks & Talks’ with my best friends, teaching ethics, and developing my interactive, hopefully, helpful website, have also provided me with a meaningful life and reasons to live . . . for now. . .

I call the bear

From afar

I stare

Into its eye

I dare

To live

A little longer…

Hi: I am not sure when my goodbye party will take place, 1 month, 1 year, 10 years or… Here is my ready to go invitation. Your feedback or thoughts on the invitation is welcomed.

July/2023

OZ

An Eskimoe’s tale describes that when the elderly can no longer contribute to the village they are put out on the ice so the polar bears eat them and the young villagers hunt the bear and survive. In our modern world, where 50% of the medical costs accrue in the last couple of years of elderly life, the elderly eat the bear.

Trees Die Erect

When I walk on the ice

I enter a wilderness of the heart

I'm throwing the dice

On my own behalf

Embracing Spirit

Honoring the Transition – Come and Join Me in a Goodbye Celebration

You are invited to join me in celebrating my transition. I’d rather not have any crying or bemoaning what a perfect saint I am. Instead, we’ll sing songs, read poetry, play music, dance, speak from the heart, and much more…

I love my life, how I have lived, the choices I’ve made, even my conscious choice of words I used and phrases I refused to use—admittedly with very little regard to what many of you thought, felt or considered inappropriate, impolite, uncivil, or worse…!

For the most part I have lived my life as if every day is or may be my last day on earth. I’ve had numerous encounters with death throughout my life, most by choice and others by circumstance. I never considered death a failure. My mother had a hand in teaching me that. A phrase she repeatedly told us was, “Trees die erect.” It summed up how she lived so perfectly that we had it etched on her gravestone.

I have a deep appreciation for your tolerance of me, even when you thought me offensive, insensitive, controlling, inconsiderate, full of myself or simply dumb. None of you slapped me when I stupidly declared, more than once, “Even when I am wrong, I am right.”

When I upset you, as I’m sure I often did, in my mind it was about ‘doing good’ or having, what Ilan repeatedly called ‘a teaching moment.’ Admittedly, even this gathering is a ‘teaching moment.’

So let’s celebrate, rejoice, and have fun –

Ofer

You are invited to, privately, share your reaction/s to this ‘Invitation’ here.

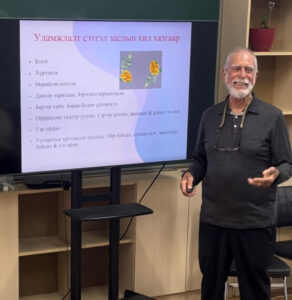

Another Mountain Scaled: Motorcycling in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert & Visit DMZ in S. Korea

In May, 2024 my son, Eitan, my nephew, Tal and I went on yet another off-road challenging and exciting motorcycle adventure, this time, in the awesome remote magical Gobi Desert in Mongolia. For many years I have been intrigued with the 12th century phenomenal-legendary-controversial Mongolian leader, Genghis Khan.

Sample of the riding off-road motorcycles in the Gobi Desert. I trained intensely for this highly challenging exiting adventure. The Gobi Desert was awesome in its beauty, enormous size, challenging bumpy terrain, millions of horses, camels, cows, sheep, goats, and hundreds of yurts widely spread apart over the huge gorgeous desert. As expected, both Eitan and I took some falls… but live to tell our story.

Sample of the riding off-road motorcycles in the Gobi Desert. I trained intensely for this highly challenging exiting adventure. The Gobi Desert was awesome in its beauty, enormous size, challenging bumpy terrain, millions of horses, camels, cows, sheep, goats, and hundreds of yurts widely spread apart over the huge gorgeous desert. As expected, both Eitan and I took some falls… but live to tell our story.

I was super excited that I was invited to present in person and via zoom on May 11, 2024 in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia (with simultaneous translation into Mongolian), for Mongolian psychologists, educators, social workers, and legal professionals on “Applied Psychological Ethics”. (The course announcement in Mongolian.)

I was super excited that I was invited to present in person and via zoom on May 11, 2024 in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia (with simultaneous translation into Mongolian), for Mongolian psychologists, educators, social workers, and legal professionals on “Applied Psychological Ethics”. (The course announcement in Mongolian.)

In a once of a life-time experience I was also invited to be a co-therapist for a highly educated Mongolian client, who spoke English well and requested me to join her therapy after a short exchange in the waiting room.

In a once of a life-time experience I was also invited to be a co-therapist for a highly educated Mongolian client, who spoke English well and requested me to join her therapy after a short exchange in the waiting room.

The last part of the trip I fulfilled another dream of mine and went (with Tal) to the famous, unique and “ultimate boundary” Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between South and North Korea.

The last part of the trip I fulfilled another dream of mine and went (with Tal) to the famous, unique and “ultimate boundary” Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) between South and North Korea.

Riding in the Gobi Desert

An adventure forged in the shadows of Genghis Khan

A contrast, then, in speed and serenity

Space, and time

The present, and the past

Theme #2: Military Experience

Theme #3: My Family & My Health

Theme #4: Questioning Authority, Challenging Accepted Truths & Debunking Myths

Theme #5: Psychology of war – The Love of Hating

Theme #6: Adventures & World Wide Travel

Theme #7: On Good Rules & Bad Rules: Pushing the Limits & Freedom Seeking

Theme #8: My Moral Junctions

Theme #9: Looking at Death Straight in the Eyes

Theme #10: Professional Psychology, Zur Institute & Professional Achievements

Theme #11: On Men, Women, Gender Role and Gender Relationships

Theme #12: At 70’s: Next Mountains to Scale

Theme #13: Amazement! I am still here