Peace & Justice in Mother’s Milk

I was born in Israel in 1950 to pioneer parents. My mother, a German Jew, was an intellectually rigorous psychologist. My father, an Hungarian Jew, was gentle and poetic but also a labor organizer and engineer.Both had lost most of their families in the Holocaust. Together, they were a visionary, optimistic, determined, and idealistic pair who mirrored the exciting tenor of the times in Israel as the new nation was born from the ashes of the Holocaust. It was only natural that concerns with justice, peace, integrity, compassion, and fairness were discussed daily around our dinner table with lively discussions about social justice, peaceful co-existence with neighboring Arab countries, and the rights of women, Jewish immigrants from Arab countries, and Israeli Arabs.

Born in Israel

To inspiring, loving parents

My destiny molded in their values of justice, compassion & peace

Like a ship beginning a voyage of self-discovery

My parents, the anchors of good deeds & righteousness

my port of calling,

my dock of endless, enduring love.

I was her

‘Kilometers Sex Chasers’ & ‘Hopeful Miles’

We were housed in a ‘quiet’ military base in the Arava desert area, by the Jordanian border, where Israeli male and female soldiers served alongside each other. It was 1970, I was a lieutenant and 2nd in command of the base and became good friends with Miri, (not her real name) an intelligent, gorgeous female soldier who was being consistently pursued by men of all ranks on the base. We developed a deep and fun relationship discussing how men were looking at her, making comments, inviting, suggesting, reaching out and touching her inappropriately.

As our friendship deepened, she shared with me the various ‘games’ she had been playing, in fact, toying with the male soldiers who pursued her. When they offered to take her for a spin in the desert in their Jeeps or other macho military vehicle, she would keep track of how far they each drove before they began to sexually pursue her until they finally, disappointedly, gave up, turned around, and drove back to the base. She described in rich detail how some started with sweet talking, while others reached straight for her breasts. Some pretended to be interested in her philosophy of life while others took a short cut straight to her crotch. We discussed the pursuers’ strategies and embellished it with fun mathematical (miles) precision.

We established a practice where she would record the vehicle odometer as soon as she entered the vehicle with any ‘hopeful pursuer,’ and then again when they returned to base. In our bemused conversations we ranked the soldiers and officers by their ‘hopeful miles’, i.e., how far they drove the vehicle before they gave up and turned back.

- The shortest distancers, most impatient ones, were nicknamed ‘the 5 kilometer (3 miles) impatient chasers’. Obviously, these were highly entitled and impatient men who were generally on the crude side.

- We named the next level ‘the 20 kilometers (13 miles) pretenders.’ They would take more time to drive and more effort to seduce her than the first group before they realized the futility of their aspirations.

- The most ‘persistent’ few were crowned ‘the 50 kilometer (30 miles) determined pursuers.’ This group drove 30 miles, some even off roads, before they gave up and turned back. These 30 mile insistent pursuers sometimes read her poetry, confessed their longtime attraction to her, and romantically pointed at the stars, moon, mountains or an occasional nocturnal desert animal. Their patience generally wore off at 20 miles and poetry would often shift to an aggressive sexual touch around mile 25 to 30.

Obviously, we paid careful attention to her physical safety in these ‘adventures’, primarily by sorting out ahead of time who she agreed to run the ‘miles experiment’ on. She also had her own small military radio on her (in that pre-cellphone era) where she could, if necessary, directly connect with me and I could track her physical location.

She never had sex with any of the hopeful pursuers. It was a game that some may legitimately claim was unfair, unkind, manipulative or even cruel… It may come as no surprise to some that she and I never physically sexualized our friendship. Obviously, our measuring games, ranking the officers and soldiers by their hopeful miles and follow up conversations were rather sexy in and of themselves. In fact, one may say, it was as sexy as traditional sex… if not even more…

Breaking Up With My Girlfriend So I Would Be Free to… Die

The highly trained paratrooper unit, in the 1973 (Yom Kippur) war, that I was part of was stationed by the Sea of Galilee because Central Command did not know where it wanted to deploy us. The Israeli army was sustaining severe casualties to soldiers, as well as damage to tanks and armed vehicles as a result of the new shoulder rockets supplied to the Egyptian army by the Soviets. Knowing that the central command was going to deploy us to one of most dangerous combat areas, there was a heightened likelihood of dying or being severely wounded in battle. Knowing this, I decided to break off my two-year relationship with my dear, sweet, loving girlfriend. As odd as it sounds in retrospect, at the time, I did so for what I considered to be two clear reasons: First: I wanted to be able to go to battle and face bullets, bombs and… death without needing to think of or worry about who I was leaving behind. It meant to me that I was free to die. It seemed to me that if it came to that it would help me face the bullets and die in peace. Second: I thought it was the most loving and unselfish thing to do, as it would free my girlfriend from worrying about me since we would no longer be lovers. Needless to say, this peculiar way of thinking, as many have pointed out to me later in life, was one more manifestation of my eccentric way of doing the ‘right thing.’ Nevertheless, at the time, it did give me a true sense of freedom to face death head-on without fear, hesitation or worry. I later learned how broken-hearted and upset my girlfriend was with my odd way of thinking and of loving, by breaking off the relationship in order to ‘protect her.’

It was my way, to face death

Head on, to protect

Those I loved and spare them from any hurt or pain

To leave her would enable me to

Fight and not have my girlfriend

Worried about my safety and well-being

That she could be protected from fear

I could fight, by doing good

And the right thing

Discovering the Power of Women on the Male Psyche

As we were waiting to be deployed in the 1973 (Yom Kippur) war, I noticed that almost all my fellow officers were impatient to engage in battle even though it was clear that doing so was likely to result in high casualties to our unit – and, of course, to ourselves. In fact, some men even tried to exert influence on the high command to get us deployed. Believing that the war could have been prevented, I was more ambivalent. I felt spacious with time in our ‘wait and see’ position by the gorgeous Sea of Galilee, and wondered what the soldiers were actually thinking in anticipation of being at war and at risk for their lives. So I started questioning soldiers about their attitude, and almost of all of them said they unequivocally wanted to engage in battle, regardless of the high probability of injury or death. As soon as I realized this, I went out again, this time with my notebook, asking the bored and anxious ‘to-be-deployed’ soldiers why they were so eager to go to war and risk their lives. Aside from the cliché response of wanting to defend the country, when I invited them to go deeper most of them said they did not want to come back home without a war story. Now my curiosity skyrocketed and the researcher in me could not wait to go back and ask the soldiers, “Who is this story for?” The response took me completely by surprise. They did not want to come back home without a war story to tell their wives, sweethearts and girlfriends. It was a truly (personal and academic) ‘aha-moment’ realizing the invisible powerful presence of women among the battle-ready paratroopers, such that they were willing to risk their lives rather than come home without a story of heroism of some sort.

As an analyst, even then,

I researched the behavior

of the soldiers who I commanded

and asked:

why are you risking your lives to go to war?

The answer they gave was baffling.

The story the soldiers told me

was they did this for women,

whose presence permeated the air,

who contributed to the war effort,

more than I ever surmised or thought possible.

Rethinking the Myth of the “Warrior and the Beautiful Soul”

The fascinating and surprising revelation of the invisible yet powerful presence of women among us heroic paratroopers has stayed with me for a long time. Years later, when I ‘converted’ to psychology, I chose to explore the intriguing psychological complexities of relationships between men, women and war. Studying the commonly held beliefs, such as “men are more violent than women,” “women are the peaceful gender,” or “if women were running the world there would be no war,” and being aware of my contradictory experience with my paratrooper unit gave birth to my doctoral dissertation, as well as to more extensive post doctorate research, publications and lectures on the topic of The Complex and Intriguing Relationships Between the Warrior and the Beautiful Soul. My research pointed to the obvious facts that some of the most war-mongering heads of states have been women, such as Indira Gandhi of India, Margaret Thatcher of England and Golda Meir of Israel. It also led me to explore the complex, rarely discussed, and certainly politically incorrect topic of the interactive nature of domestic violence in heterosexual relationships and in lesbian and gay relationships. While hard to acknowledge, admit or digest, increased number of studies have determined that the rate of Same-Sex Intimate Partner Violence (SSIPV) among lesbian couples is, surprisingly—or, some may argue, not surprisingly—higher than the rate of intimate partner violence (IPV) [i.e., men violent against women] among heterosexual couples. More broadly I walked into the equally politically incorrect minefield exploring the role of some victims in their own victimization.

The relationship, between warriors & beautiful souls

Between men who started wars,

and women who were to be passive, ‘peaceful’

But often, in fact, were not

Apparently, women could be war-mongering

in thoughts, wives, girlfriends and as leaders

and so the waters were muddied

women were not always peaceful

or passive bystanders to violence,

and to the world, around them.

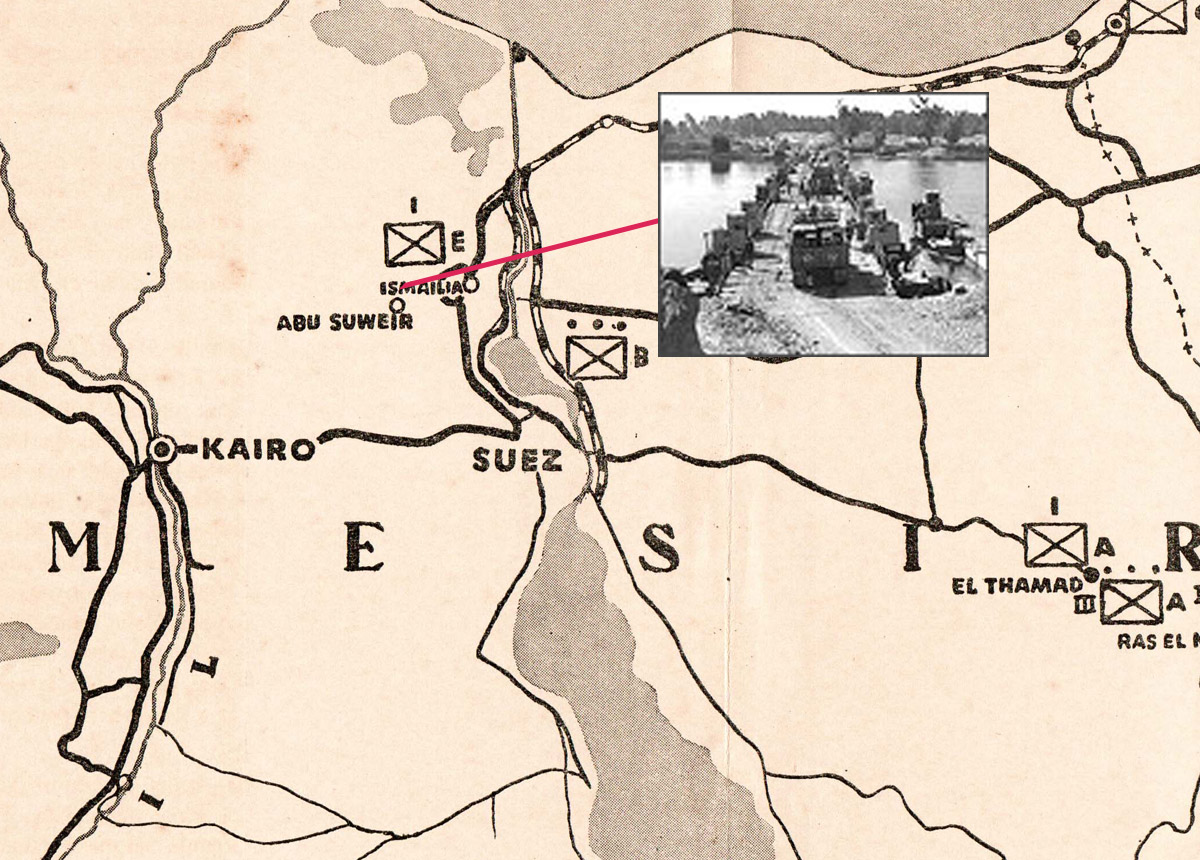

Thumbing My Nose at Death on a Bridge of Fire

Towards the end of the 1973 war, my unit was finally deployed. We were assigned to cross a bridge across the Suez Canal and head north towards the revered city of Ismailia. At this point of the war the Egyptian army was highly concerned that if the Israeli Armed Forces crossed the Suez Canal, they would subsequently have a clear path to Egypt’s capital, Cairo. As a result, the Egyptian army was defending the bridge that my unit had been assigned to with all their remaining military might, relying on intense artillery bombardments, air force bombings, and anti-tank guided missiles to deter the incoming Israeli army. When we arrived, Israeli tanks, personal carriers and jeeps were on fire and literally flying off the bridge. It was an intense game of chicken between the Egyptian bombings and the Israeli military engineering unit, which was rapidly rebuilding and repairing the repeatedly hit and damaged bridge. Amazingly they were able to keep rebuilding despite the catastrophic losses they were suffering.

Then, I received my orders: we were commanded to cross this fiery strip and move deeper into Egypt. While the rest of my unit quickly jumped into vehicles and sped as fast as they could into the clouds of smoke that covered the bridge, my recklessness, bravery and perhaps my stupidity spurred my buddy and me to cross this death zone by foot. As fire and metal rained down around our unprotected bodies, we sarcastically argued over who would be the first to die, and who would get to put a wreath on the grave of the other at the prestigious famed national military cemetery on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem. Halfway across the bridge I suddenly felt compelled to stop. A strange sense of calm and quiet came over me despite the deafening bombs and missiles exploding all around. Almost engulfed by the chaos and destruction, I looked up at the sky and extended a defiant middle finger to God, a gesture by which I was telling Death, “I do not fear you!”

This attitude of fearlessness towards death, which has harmoniously and consistently coexisted with my deep reverence for life, has revealed itself in multiple ways throughout my life, such as in my predilection for evacuating hospitals against medical advice, diving the magical but lethal Blue Hole, shooting the light bulb, challenge-riding a motorcycle at the Himalayas by 4,000ft drops and many other death-defying ventures. My mother vowed she wanted to ‘die erect,’ so perhaps there’s a strain of this mentality I inherited from her!

Even as I walk, surrounded by flames

On this Bridge of Fire

You, death, will not win!

Though you may try to burn my aching body

You will never singe my soul – my essence

Oh death, You will not defeat me!

When my Calf was Blown Off in Battle of Ismailia: Am I a War Hero or My Parents’ Sacrificial Lamb?

In the waning minutes of the Yom Kippur (1973) war, I once again found myself at the aweinspiring boundary between life and death during the Battle of Ismailia when I was seriously wounded after most of my left calf was blown off and I collapsed in complete and utter silence. The silence, as I put together months later, was partly due to the fact that I lost my hearing when the intense enemy bombing ruptured my eardrums. As soon as I collapsed into this zone of silence and injury, as if someone had literally pulled the rug from underneath me, I told myself, “I lost my leg because I should have not gone (or walked) to a war that I did not fully believe in.” (Later in life I followed up on this interpretation and explore in depth the constructs of the ‘metaphor of illness’ or the meaning of dis-eases.)

I was evacuated under heavy fire, and to my deep distress found myself in an armed vehicle, which I knew to be an easy target for the enemy’s lethal shoulder missiles. What was strange about the morphine-induced delirium I experienced during this evacuation was that I became less worried about being blown up by a lethal Egyptian shoulder missile than I was about being part of an imaginary ‘cosmic play,’ in which I was the sacrificial lamb to my peace-loving parents who were simultaneously and paradoxically against the war while proud of their ‘sacrificial hero/wounded lieutenant son.’ Years later, in an attempt to make sense of this bizarre but intriguing experience, I devoted considerable time to exploration of what is known as the Medea Complex, or the unconscious wishes of parents to kill their children as manifested by the 25 years (one generation) average of war cycles in modern times.

War hero, sacrificial lamb

In a war I did not fully believe in

My left calf, blown apart

Like the peaceful beliefs that had been planted,

like tulips in my heart

The world around me, sounds, colors

Faded in, briefly

My life, my being, my very essence

My fate, left in the balance

Between the desert and the cosmos

Idiotic Myth: “Israeli Paratroopers Don’t Get PTSD”

Right after this bizarre scene with my doctor, I started training myself to walk again. I rejected any physical therapy and spent long nights, all alone, walking on the hospital room porch, holding on to the rail, and ‘silently’ crying in pain. When I eventually went back to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem to continue my studies, I also went back to riding my motorcycle and playing basketball on the university team. The subsequent surgeon, unusually but effectively, used my performance on the basketball court as a yardstick to measure when I was ready for the next surgery. Obviously, this injury was followed by a few years of intense pain, determination, surgeries, rehab, deep contemplation, and finally, full recovery in spite of a very poor prognosis. It took me many years to attend to the traumatic aspect of the war injury & war experience and numerous other traumas I’d experienced in my lifetime and embrace the illuminating concept of Post Traumatic Growth (PTG) rather than Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Learning to walk again

alone At night

the only sound, My heartbeat

feeling intense waves of pain

Looking for an oasis of healing

A spring inside of myself

A determination to heal, spiritually,

Physically and emotionally.

“All of you guys are missing some parts!”

Two young ones, not quite adults, still nourished by the springtime of possibilities. We held hands and while walking the coast-line of the Red-Sea, immersed in the calm beauty of the sunset, enjoyed the silence of getting to know each other. She was a 19 year old young Israeli woman. I was a few years older and we had just met. We touched each other softly with a sense of innocence and wonder, more exploratory and curious than sexual. We sat with legs crossed, her head on my shoulder, as we watched the slow decent of the sun. Her soft fingertip touch came to the place where my calf was blown off in the war. She briefly paused and broke the silence by casually offering up: “All of you guys are missing some parts, aren’t you?” Then, she continued to silently and gently stroke my leg. She said it as a simple matter of fact. She could equally have said “The ocean temperature is moderate.” It was a powerful, insightful and profoundly sad moment for me. While, like most of my fellow soldiers, I was still in denial of the profound traumatic impact of my battle experience and war injury on me, it was painfully clear to me that this young woman was already completely resigned and profoundly aware of the, so called “parts” that so many of us, young men – soldiers, “were missing”.

“Missing some parts”

Parts suddenly removed

Limbs blown off

Our souls not quite intact,

Grappling with a broken body

From the injuries of yet, another war

Jesus, Magdalena, Jean and… the Thermometer

It was 1978 and I was conducting fish pond research at a lab by the Sea of Galilee. The lab was situated in a uniquely historical and spiritually potent locale. Just a quarter mile to the south was a monument marking the sacred place where Jesus healed Magdalena and Magdalena, according to some, graciously reciprocated and, in her own ‘Magdalena way,’ ‘healed’ Jesus. A quarter mile to the north was the location where Jesus walked on the water and miraculously multiplied two fish and five loaves of barley bread into enough to satisfy 5,000 people with twelve baskets remaining. This is when I met a bright and creative woman, Jean, in Jerusalem and we embarked on a few months of intense, creative and often hilariously creative letter writing (it was 1978, before e-mails and texts). After a few months Jean moved in with me in the gorgeous historic village of Rosh Pina. I was still magically and mysteriously drawn to East Africa. I knew that when I could no longer run my fish pond experiments in the winter when the water temperature in the experimental ponds would dip below 70°F, I would be heading back to East Africa for the summer there. Creative Jean, who could write a good story of any interesting life event, made a habit of coming down to my experimental ponds with a thermometer in hand every few days, precisely and systematically detecting how many degrees were left for our relationships. She regularly announced, in a sad yet sweetly accepting or even romantic tone, “I have 2 degrees left before my relationship with Ofer is over” or “My love with Ofer has barely half a degree left.”

The miracle of bread and wine

Walks on the magic waters

of loving her

As she counts and recounts

Her love

In degrees of separation

From Fish to People: On Mothers, Women &… War

At 29 years old, I moved to the US to do my M.A. in counseling at Lesley College in Cambridge, Massachusetts, ‘slightly’ shifting my career interests and path from fish and oceanography to psychology, psychotherapy and counseling. Within psychology I was interested in learning about the healing process for individuals, couples, families, communities and cultures. Initially I was intrigued by the psychology of peace and violence on all levels from the individual to the cultural. I was interested in the roots of war and the prerequisites of peace and explored a variety of theories on these topics. I was especially intrigued with how men and women co-participated in the making of war, or what I called “The role of women in the making of war”, and similarly how parents and their young adult children co-created war systems. (Later, I expanded these interests into thinking about the tensions between life, love, and mortality.)

The deep watery realms of the soul

Where fish become emotions

Where riffs become rifts

Where women’s love shifts

By the seduction of war

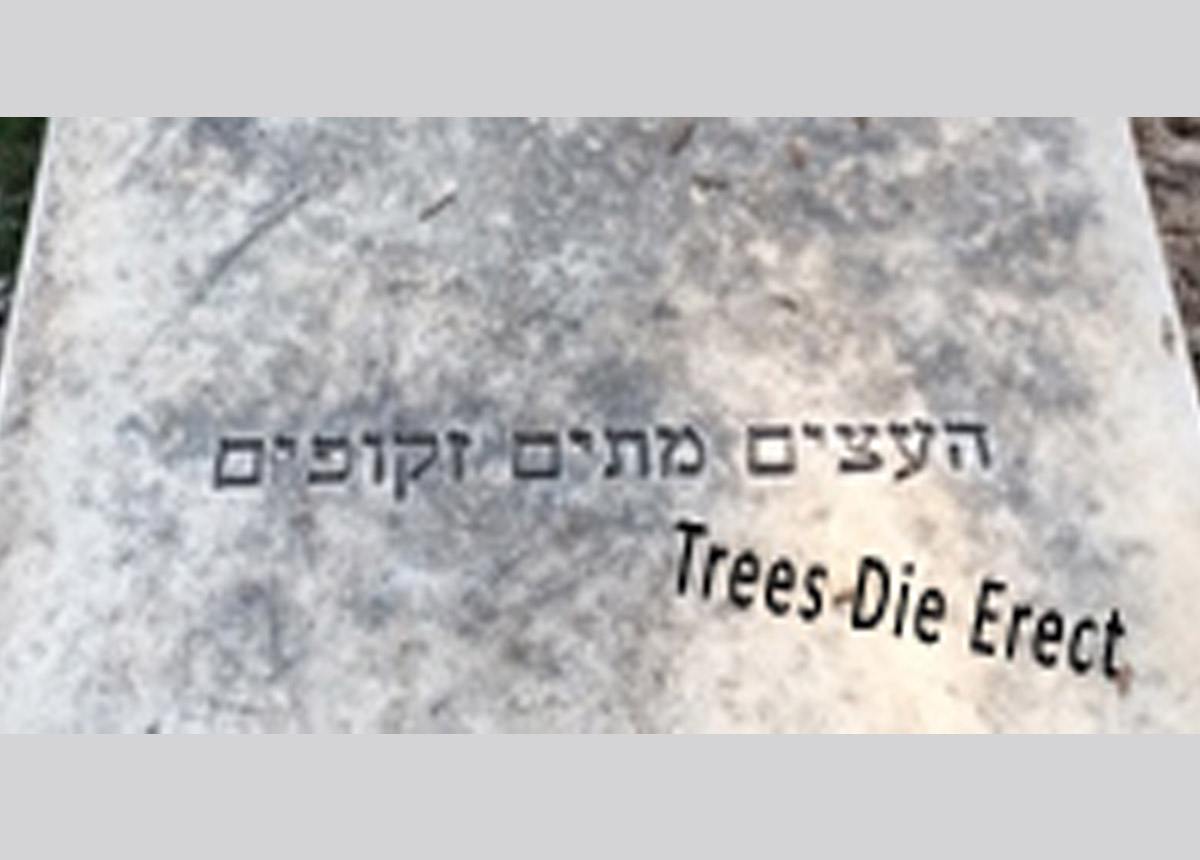

“Trees Die Erect” – Mother Parted Exactly as She Planned

I continued my work, exploring the roots of war and promoting peace, which led me to literature that discussed the meaning of the fact that the average frequency of war is 25 years, which corresponds to the span of a generation. The theory posited the puzzling and odd idea that war may be the unconscious wish and impulse of parents to kill their children, or what is also known as the Medea Complex. I asked my mother her thoughts on this idea and did not hear back from her for a couple of months. Then one day, I got a package from her with probably all the available literature on this obscure topic. She noted that compiling this literature was one of the most difficult challenges she had ever faced. That was the last correspondence I had from her as she died soon after from her second heart attack in November 1982 at age 68. Mother repeatedly told us that she neither wanted to slow down in old age nor have a prolonged death. So on her gravestone we engraved her own words -“Trees Die Erect”.

One never to slow down

An intellectual giant

A loving mother

A questioning soul

Who didn’t wish to linger too long between life and death,

between sunshine and shade

So on her gravestone we wrote the words

“Trees Die Erect”

Getting my Ph.D. – Studying the “Love of Hating”

In 1984, at 34 years old, I received my Ph.D. from the Wright Institute in Berkeley, CA. My dissertation centered on the dynamics of how men and women view and co-create warfare, and called sharply into question the almost universal belief that only men are inherently warlike, while women are inherently peace-loving. Subsequently, in a paper, “The Love of Hating”, I refuted another faulty belief – that war has no intrinsic appeal and is only a necessary evil or last resort – and explored the conscious and unconscious attractions of war.

A time of immense pride

To explore unquestionable beliefs

Of war and peace

Shade and sunlight

Perhaps in the shadows

The truth would lie

I’d embark

On my lifelong quest

To examine the faulty notion

That men were mainly warlike

While women were capable of only peaceful actions

Re-Thinking “Don’t Blame the Victim”

In the mid 1990’s, I took on debunking the myth that all victims are always innocent and invited people to re-think the then prevalent belief in the dictum, “Don’t Blame the Victim.” While some victims are truly innocent (e.g., abused children) others thrive on being victims. The victim’s stance is a powerful one and was erroneously framed as: The victim is always morally right, neither responsible nor accountable, and forever entitled to sympathy. That perception has since changed to some degree, I am pleased to say.

The heart that goes out

To the victim

Is the heart that extends its sight

To see the victim as a powerful creator:

Both hurt

And with might

Eitan’s Bar Mitzva Ritual on Masada & at the Desert with the Guys

In 2006 we celebrated the Bar-Mitzvah of our oldest son, Eitan, on top of the ancient and inspirational Jewish stronghold of Masada, followed by a ‘for men only’ rite of passage in the Negev Desert in Israel, where I had the dubious pleasure of jogging in 114° F heat.

A special ritual

Shared with my son

An ancient place swept by the sands of time

The sun hung high above the Negev Desert

Wrapping us in a blanket of heat

A Dream Came True: All 3 of Us, Boys, Riding Motorcycles Together

Sept. 20, 2014 – an historic day in the Zur Family as all three boys own their own bikes. The three of us celebrated by riding our motorcycles today on scenic Highway 1 along the Pacific coastline.

The dream of riding our motorcycles together

A reality now

Three boys

Cruising along Highway 1

Catching glimpses of ocean and coastline

As smiles form on our faces

A sense of comradery, a joyous adventure

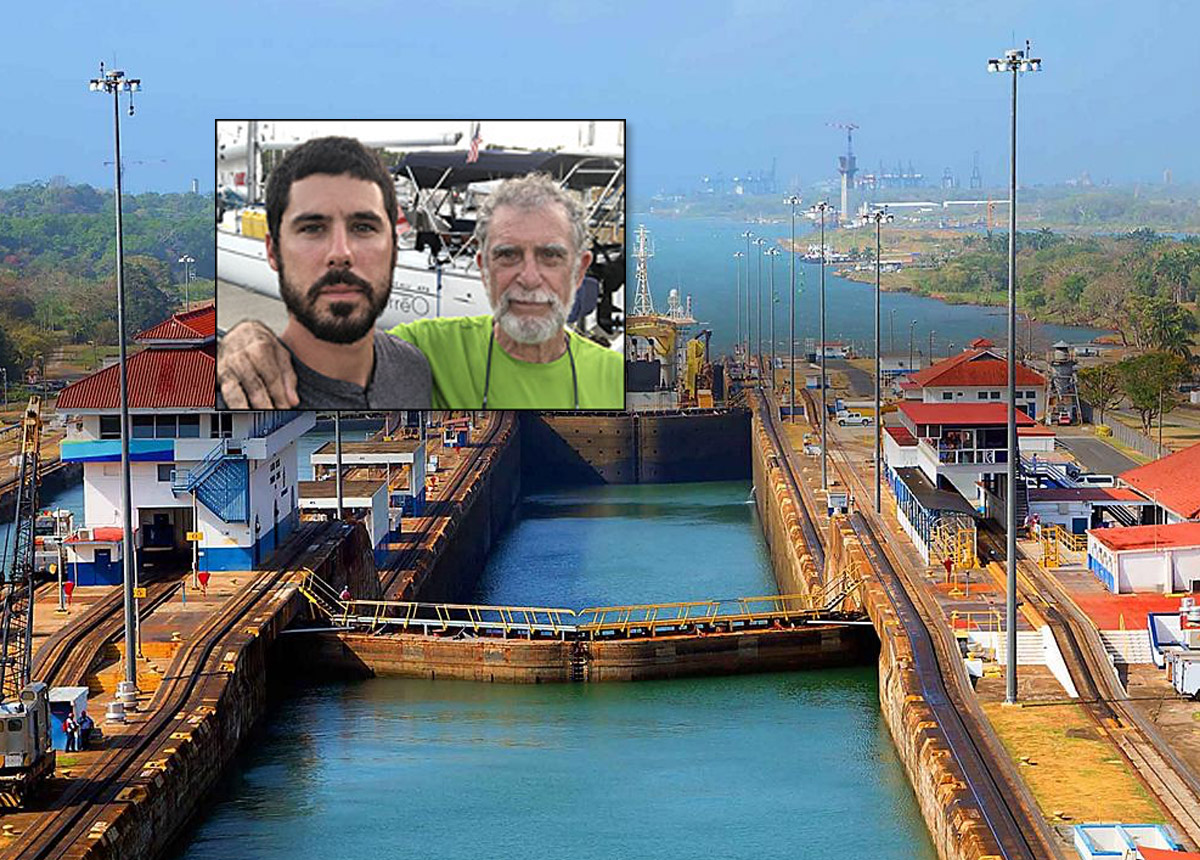

Crewing for My Son Through the Majestic Panama Canal

In 2019 I had the golden opportunity to fulfill a dream I have had since I was a 21-year-old Israeli merchant marine wishing to sail through the majestic and iconic Panama Canal. I was thrilled to be invited to crew for my son, Eitan (who lives on his beautiful 36-ft. sailboat in San Diego), who was hired to transport a 47ft sailboat from Baltimore to San Francisco. The Panama Canal certainly deserves its impressive rating as one of the top ‘Wonders of the World’. Eitan, a competent captain, led us through the 50 miles long perfectly designed three locks going up from the Atlantic Ocean side to the impressive and enormous man-made lake at the top, and then through three impeccably constructed locks down toward the Pacific Ocean side. This was an amazing, once-in-a-lifetime experience in many ways.

Fulfilling a dream

Born long ago

Sailing through the Panama Canal to crew for my son

An adventure

A wish brought to life

Looking out at the majestic waves

My heart, warm with camaraderie

and love for my son

Father-Son Now Man-to-Man: Sailing the Rhode Island Coast

Not too long after crewing for Eitan on the majestic Panama Canal in 2019, he and I joined up for another fantastic nautical journey, this one off the coast of Newport, Rhode Island. On this three-day trip I enjoyed the great pleasure of crewing for him on a 44-ft. catamaran headed to Martha’s Vineyard, passing along neighboring islands off the coast of Rhode Island.

Sailing with Eitan, just the two of us together on the magnificent Atlantic, opened a special door to our hearts, as it reminded us of the many adventures we have taken together, including kayaking 17 miles along the Na Pali Coast off of magical Kauai, climbing Mount Kilimanjaro, and many more. The meaningful connection and deep conversations we had into the night were precious beyond words. What was at one time a father to child relationship has now morphed into that of man and man.

My mind was one with the tides & the wind,

the sea had called repeatedly to me

throughout my life

carried my dreams and hopes,

and now those of my son

5 Forms of Guilt

The following are my thoughts on the different types of guilt and some of the ways in which I have experienced guilt. These are less obvious forms of guilt and go beyond lack of guilt (psychopathy) and excessive guilt (depression, anxiety, suicide, etc). As would be expected, by the age of 71, I have experienced most forms of guilt.

1. Appropriate Guilt: This type of guilt is an appropriate response to, or regret for, what we have come to understand, acknowledge or admit that we have done something wrong, unjust or immoral, or feel remorse for what we have not done. In my own life, I regret some of the ways I endangered others with the way I rode my motorcycle or shot the light bulb in the bunker, what I did or did not do in war, or was insensitive to friends’ needs.

2. Catholic Guilt – Religious Guilt: This kind of guilt is religion-induced that does not differentiate ones thoughts from their actions. Besides the Catholic church, other Christian denominations also believe people should confess to ‘sinful’ thoughts, yearnings or desires even when no actions were taken. Similarly, the ultra orthodox Jewish religion makes no distinction between ‘sinful thoughts’ and ‘sinful acts.’ I have experienced this kind of guilt as a young man when I felt guilty for internally reacting disproportionately with extreme anger.

3. Survival Guilt: This kind of guilt primarily manifests in people who have survived a life-threatening situation, such as battles during war or car accidents where others died or were severely injured. They often believe they could have done more to save the lives of others even if they could not. I have definitely felt this kind of guilt in relation to fellow soldiers who died or were heavily injured in military operations I was part of.

4. Neurotic – Toxic guilt – Persecutory guilt: This form of guilt is derived from a sense of not being a good–enough person, feeling like a failure who deserves to be punished. Persecutory guilt is a form of self-inflicted punishment

5. Existential guilt: This type of guilt can seem free-floating or unrelated to any particular situation. It is about one’s sense of accomplishment or success in addition to an awareness of the inequalities and injustices that exist in the world, such as a family member or community of people who are less capable or less fortunate than you are, or the fact that there may be people starving in Africa, or that the whales are dying off due to over hunting, pollution and other factors. When a person asks themselves “Am I doing enough to help others or help the world?” I have definitely experienced this kind of guilt combined with deep concerns for the underprivileged people worldwide, victims of unjust war, and disappearing species around the world.

The Coronavirus Pandemic exemplifies a variety of feelings of guilt that are the result of the fact that billions of people are unemployed, locked at home, or struggling with food needs, yet ‘you’ still have a job or can provide for your family. People may feel guilty because their children can’t see friends and grandparents or participate in normal activities. Perhaps someone they care for has been ill with COVID-19 or they feel guilty because a loved one has died all alone (‘coronavirus way’), and they couldn’t be there to say goodbye.

An emotion we perfected as human beings

Guilt

Is built

On so many lies

We tell ourselves

Not All Affairs Are Created Equal

Infidelity, unlike what most people assume, is neither rare, an exclusively man’s doing, nor the likely end of the marriage. Almost a third of all marriages may need to confront and deal with the aftermath of extramarital affairs. Women, men, gay, straight, young and old, all seem to be somehow engaged in affairs. Online affairs have become extremely prevalent. Marriages can get stronger when couples deal constructively with the affair. See: Infidelity & Affairs: Myths, Facts & Ways to Respond

Types of Affairs:

| 1. Conflict Avoidance | 8. Unsatisfactory Marriage |

| 2. Intimacy Avoidance | 9. Exit Affairs – Jumping off point |

| 3. Individual Existential/Developmental crisis | 10. Long Term Parallel Lives |

| 4. Sexual Addiction – Sexual Obsession | 11. Online (Most prevalent) |

| 5. Accidental – Brief – One Time Affairs | 12. Cyber Affair w/ a Sex-Robot |

| 6. Philandering | 13. Consensual |

| 7. Retribution |

Myths and Facts:

Myth: An affair inevitably destroys the marriage.

Fact: Many marriages survive affairs and many emerge stronger from the infidelity crisis.

Myth: Infidelity is rare in the animal kingdom.

Fact: Only 3% of the world’s 4,000 species of mammals are pre-programmed for monogamy.

Myth: Infidelity is rare and abnormal in our, and most other, societies.

Fact: Men’s infidelity has been recorded in most societies.

Myth: Society, as a whole, supports monogamy and fidelity.

Fact: Society gives lip service to monogamy/fidelity, but actually supports affairs. (i.e. Ashley Madison)

Myth: Men initiate almost all affairs.

Fact: Infidelity has become an equal opportunity issue in the West.

Myth: An affair always means there are serious problems in the marriage.

Fact: Research has shown that some of those who engage in affairs reported high marital satisfaction.

Myth: Infidelity is a sign that sex is missing at home.

Fact: Some unfaithful spouses have reported increased marital sex during the period of their affair.

Myth: Infidelity always has to do with a bad marriage or a withholding partner.

Fact: There are many reasons that people may choose to have an affair.

Myth: Full disclosure of all the details of the affair to the betrayed spouse is prerequisite to healing.

Fact: Giving the uninvolved partner all the X-rated details of the affair can be traumatizing.

Myth: Extramarital affairs are never consensual.

Fact: Open marriages used to be popular in the 1970s and are still around.

An affair to remember

An affair to forget

Between all the taboos

We met

For a moment of truth

On Critical Thinking: Exploring Politically and Professionally Incorrect Myths & Faulty Beliefs

Whether in psychology, oceanography, chemistry, limnology, or on ‘hot’ topics such as gender, race, victims or war, I have devoted a big part of my life to exploring the ‘given’, the unexamined truths, and often, the politically incorrect beliefs. The Following are some samples of the faulty beliefs I have challenged (and links to my writings on each topic):

- “Don’t Blame the victim” – Victims are 100% innocent

- Marital affairs are rare & signify that the marriage is ‘in trouble’

- The Myth of the “Warrior and the Beautiful Soul“: Unlike men, who are inherently warlike, women are innately peaceful

- Humans are inherently peaceful – Wars have no appeal

- Death is a failure and should be avoided at all cost

-

Oceanography is useless for fish farming and limnology is clear about the importance of mosquito larvae for fish ponds

- Blackouts are no good and to be avoided at all costs

- When in doubt, follow your instinct

- Myths & Faulty Beliefs in Psychotherapy & Counseling:

- Touch in psychotherapy is likely to lead to sex

- Therapists are always more powerful than their clients

- Once a client, always a client

- Dual or multiple relationships in psychotherapy are unethical

- You are one Borderline (BPD) away from losing your license

- The DSM (Diagnostic Statistical Manual) is scientifically based

- Risk management is at the heart of the standard of care

- Boundary crossings inevitably lead to boundary violations

The unexamined truths

Is a desert territory

Which I like to roam

With my heart

Theme #2: Military Experience

Theme #3: My Family & My Health

Theme #4: Questioning Authority, Challenging Accepted Truths & Debunking Myths

Theme #5: Psychology of war – The Love of Hating

Theme #6: Adventures & World Wide Travel

Theme #7: On Good Rules & Bad Rules: Pushing the Limits & Freedom Seeking

Theme #8: My Moral Junctions

Theme #9: Looking at Death Straight in the Eyes

Theme #10: Professional Psychology, Zur Institute & Professional Achievements

Theme #11: On Men, Women, Gender Role and Gender Relationships

Theme #12: At 70’s: Next Mountains to Scale

Theme #13: Amazement! I am still here

Before exploring ‘life after leaving,’ I want to revisit my time in Israel in the early 70s as an officer in the Israeli army. Our highly trained unit was stationed in a tremendously overcrowded, poverty-stricken, and polluted refugee camp in the occupied Gaza Strip. The camp consisted of thousands of single-story houses jammed full with multiple generations in families, and often chickens and ducks as well! The narrow streets—actually muddy alleyways—emitted the foul stink of urine and excrement from donkeys, mules, chickens, ducks and… humans.

Before exploring ‘life after leaving,’ I want to revisit my time in Israel in the early 70s as an officer in the Israeli army. Our highly trained unit was stationed in a tremendously overcrowded, poverty-stricken, and polluted refugee camp in the occupied Gaza Strip. The camp consisted of thousands of single-story houses jammed full with multiple generations in families, and often chickens and ducks as well! The narrow streets—actually muddy alleyways—emitted the foul stink of urine and excrement from donkeys, mules, chickens, ducks and… humans. I despised myself for not protecting this woman and her children, for not standing in front of the Israeli bulldozer the way the heroic ‘Tank-Man’ stood in front of the tanks in Tianaman square in China.

I despised myself for not protecting this woman and her children, for not standing in front of the Israeli bulldozer the way the heroic ‘Tank-Man’ stood in front of the tanks in Tianaman square in China.