On Being a War Hero – Groomed to Sacrifice

The messages drifted in, almost like elevator music entering my subconscious mind, such good food for the developing ego “Be a man! Be admired! Be a war hero.” As a skinny young boy, I recall standing a little bit taller, sticking my chest out a bit more and imagining basking in the admiration of women and children. I was destined to be a war hero! We were groomed to sacrifice. I was 23-years-old when the 1973 war between Israel and the surrounding Arab countries started with a massive surprise attack on Israel. Israel—the country my parents wove every hope and dream into, the post-holocaust safe place for the children of our tribe and the generations to follow. Invaded by the surrounding Arab countries from the north, west, and south, Israeli casualties were mounting fast and a sense of panic and terror engulfed the country. All reserve soldiers were immediately called for military service. I was strongly torn. On the one hand, I believed then and still do, that Israel has the right to exist and obviously has the right to defend itself. This being a given, I felt I should join the armed forces to fight for Israel’s very survival. On the other hand, I also strongly believed that the war could have been prevented if Israel had given back (as it should have) the occupied territories that it had conquered in the 1967 war. But on yet ‘another hand’ I wanted to be a war hero. I did not want to stay behind with the women, children, the elderly and disabled. So in the end, even though I was not drafted or called to serve, I was strongly compelled to join the armed forces fighting for Israel’s survival, in a war that could have been avoided. At my own initiative I was assigned to a highly esteemed paratrooper unit. Following that initial egoic impulse, I became a war hero.

I was groomed to serve a country

a land where Jews re-planted roots

Together grown from springs of hope

And tenacity

Yet torn was I, the desire to be a hero

But to sacrifice myself, some of my values

Made question my identity, my sacredness

My country’s vision, my vision of self

Breaking Up With My Girlfriend So I Would Be Free to… Die

The highly trained paratrooper unit, in the 1973 (Yom Kippur) war, that I was part of was stationed by the Sea of Galilee because Central Command did not know where it wanted to deploy us. The Israeli army was sustaining severe casualties to soldiers, as well as damage to tanks and armed vehicles as a result of the new shoulder rockets supplied to the Egyptian army by the Soviets. Knowing that the central command was going to deploy us to one of most dangerous combat areas, there was a heightened likelihood of dying or being severely wounded in battle. Knowing this, I decided to break off my two-year relationship with my dear, sweet, loving girlfriend. As odd as it sounds in retrospect, at the time, I did so for what I considered to be two clear reasons: First: I wanted to be able to go to battle and face bullets, bombs and… death without needing to think of or worry about who I was leaving behind. It meant to me that I was free to die. It seemed to me that if it came to that it would help me face the bullets and die in peace. Second: I thought it was the most loving and unselfish thing to do, as it would free my girlfriend from worrying about me since we would no longer be lovers. Needless to say, this peculiar way of thinking, as many have pointed out to me later in life, was one more manifestation of my eccentric way of doing the ‘right thing.’ Nevertheless, at the time, it did give me a true sense of freedom to face death head-on without fear, hesitation or worry. I later learned how broken-hearted and upset my girlfriend was with my odd way of thinking and of loving, by breaking off the relationship in order to ‘protect her.’

It was my way, to face death

Head on, to protect

Those I loved and spare them from any hurt or pain

To leave her would enable me to

Fight and not have my girlfriend

Worried about my safety and well-being

That she could be protected from fear

I could fight, by doing good

And the right thing

Discovering the Power of Women on the Male Psyche

As we were waiting to be deployed in the 1973 (Yom Kippur) war, I noticed that almost all my fellow officers were impatient to engage in battle even though it was clear that doing so was likely to result in high casualties to our unit – and, of course, to ourselves. In fact, some men even tried to exert influence on the high command to get us deployed. Believing that the war could have been prevented, I was more ambivalent. I felt spacious with time in our ‘wait and see’ position by the gorgeous Sea of Galilee, and wondered what the soldiers were actually thinking in anticipation of being at war and at risk for their lives. So I started questioning soldiers about their attitude, and almost of all of them said they unequivocally wanted to engage in battle, regardless of the high probability of injury or death. As soon as I realized this, I went out again, this time with my notebook, asking the bored and anxious ‘to-be-deployed’ soldiers why they were so eager to go to war and risk their lives. Aside from the cliché response of wanting to defend the country, when I invited them to go deeper most of them said they did not want to come back home without a war story. Now my curiosity skyrocketed and the researcher in me could not wait to go back and ask the soldiers, “Who is this story for?” The response took me completely by surprise. They did not want to come back home without a war story to tell their wives, sweethearts and girlfriends. It was a truly (personal and academic) ‘aha-moment’ realizing the invisible powerful presence of women among the battle-ready paratroopers, such that they were willing to risk their lives rather than come home without a story of heroism of some sort.

As an analyst, even then,

I researched the behavior

of the soldiers who I commanded

and asked:

why are you risking your lives to go to war?

The answer they gave was baffling.

The story the soldiers told me

was they did this for women,

whose presence permeated the air,

who contributed to the war effort,

more than I ever surmised or thought possible.

Rethinking the Myth of the “Warrior and the Beautiful Soul”

The fascinating and surprising revelation of the invisible yet powerful presence of women among us heroic paratroopers has stayed with me for a long time. Years later, when I ‘converted’ to psychology, I chose to explore the intriguing psychological complexities of relationships between men, women and war. Studying the commonly held beliefs, such as “men are more violent than women,” “women are the peaceful gender,” or “if women were running the world there would be no war,” and being aware of my contradictory experience with my paratrooper unit gave birth to my doctoral dissertation, as well as to more extensive post doctorate research, publications and lectures on the topic of The Complex and Intriguing Relationships Between the Warrior and the Beautiful Soul. My research pointed to the obvious facts that some of the most war-mongering heads of states have been women, such as Indira Gandhi of India, Margaret Thatcher of England and Golda Meir of Israel. It also led me to explore the complex, rarely discussed, and certainly politically incorrect topic of the interactive nature of domestic violence in heterosexual relationships and in lesbian and gay relationships. While hard to acknowledge, admit or digest, increased number of studies have determined that the rate of Same-Sex Intimate Partner Violence (SSIPV) among lesbian couples is, surprisingly—or, some may argue, not surprisingly—higher than the rate of intimate partner violence (IPV) [i.e., men violent against women] among heterosexual couples. More broadly I walked into the equally politically incorrect minefield exploring the role of some victims in their own victimization.

The relationship, between warriors & beautiful souls

Between men who started wars,

and women who were to be passive, ‘peaceful’

But often, in fact, were not

Apparently, women could be war-mongering

in thoughts, wives, girlfriends and as leaders

and so the waters were muddied

women were not always peaceful

or passive bystanders to violence,

and to the world, around them.

Thumbing My Nose at Death on a Bridge of Fire

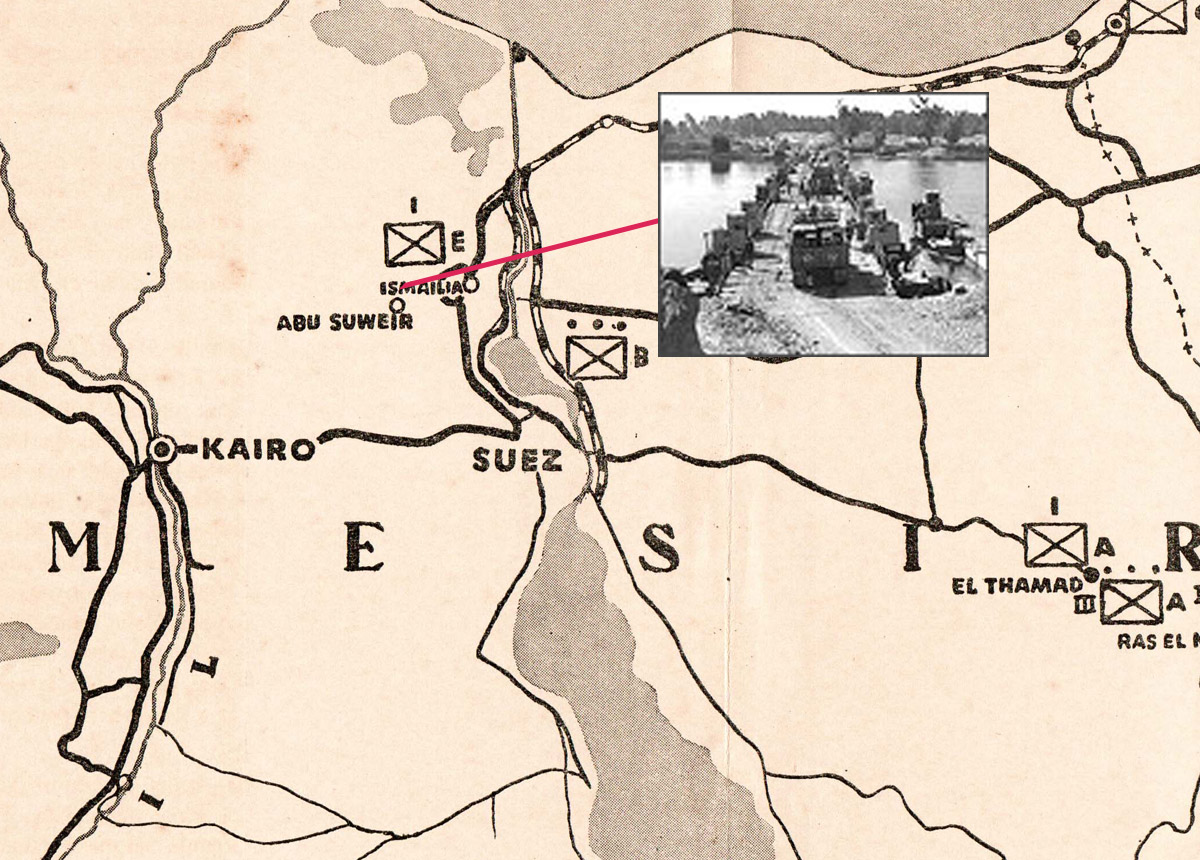

Towards the end of the 1973 war, my unit was finally deployed. We were assigned to cross a bridge across the Suez Canal and head north towards the revered city of Ismailia. At this point of the war the Egyptian army was highly concerned that if the Israeli Armed Forces crossed the Suez Canal, they would subsequently have a clear path to Egypt’s capital, Cairo. As a result, the Egyptian army was defending the bridge that my unit had been assigned to with all their remaining military might, relying on intense artillery bombardments, air force bombings, and anti-tank guided missiles to deter the incoming Israeli army. When we arrived, Israeli tanks, personal carriers and jeeps were on fire and literally flying off the bridge. It was an intense game of chicken between the Egyptian bombings and the Israeli military engineering unit, which was rapidly rebuilding and repairing the repeatedly hit and damaged bridge. Amazingly they were able to keep rebuilding despite the catastrophic losses they were suffering.

Then, I received my orders: we were commanded to cross this fiery strip and move deeper into Egypt. While the rest of my unit quickly jumped into vehicles and sped as fast as they could into the clouds of smoke that covered the bridge, my recklessness, bravery and perhaps my stupidity spurred my buddy and me to cross this death zone by foot. As fire and metal rained down around our unprotected bodies, we sarcastically argued over who would be the first to die, and who would get to put a wreath on the grave of the other at the prestigious famed national military cemetery on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem. Halfway across the bridge I suddenly felt compelled to stop. A strange sense of calm and quiet came over me despite the deafening bombs and missiles exploding all around. Almost engulfed by the chaos and destruction, I looked up at the sky and extended a defiant middle finger to God, a gesture by which I was telling Death, “I do not fear you!”

This attitude of fearlessness towards death, which has harmoniously and consistently coexisted with my deep reverence for life, has revealed itself in multiple ways throughout my life, such as in my predilection for evacuating hospitals against medical advice, diving the magical but lethal Blue Hole, shooting the light bulb, challenge-riding a motorcycle at the Himalayas by 4,000ft drops and many other death-defying ventures. My mother vowed she wanted to ‘die erect,’ so perhaps there’s a strain of this mentality I inherited from her!

Even as I walk, surrounded by flames

On this Bridge of Fire

You, death, will not win!

Though you may try to burn my aching body

You will never singe my soul – my essence

Oh death, You will not defeat me!

Monkey & Me: Respect For & Identification With the Enemy

After a few days of cautiously moving towards enemy lines in the 1973 war, our military unit became the target of artillery shells. Some fell to the left of us, some to the right, some in front of us where we were headed, and some behind us, where we had been an hour ago. In a curious, fascinating, and yet terrifying pattern, the shells began to gradually close in on us in a perfect lethal circle, closer and closer on all sides. As our unit paused under a grove of high palm trees, the shells began falling so close to our group that it became obvious that the artillery weapons were being systematically directed by someone or something that was aware of our location. Was there an unseen aircraft tracking us, a satellite, or an eye in the sky?

As we frantically tried to figure out who/what was doing this we peered at the sky through the fronds of the palm trees above and suddenly spotted what in some military jargon is called a “monkey” — a perfectly camouflaged Egyptian soldier sitting atop one of the trees, trying to blend in with the thick canopy. We instantly realized that he was the one providing his fellow artillery soldiers miles away with the exact location of our unit. Within a milli-second, about 20 to 30 solders aimed and rapidly shot their M-16’s automatic guns at him. By the time he hit the ground he had several hundred bullet holes in him. Needless to say, he did not suffer much. A couple of distressed, frightened and enraged soldiers even shot a few more rounds into the lifeless bleeding body.

I looked at this bullet-ridden corpse and experienced an upwelling of admiration, respect, and even awe, for this man who had directed his artillery on our unit… and in the end, on himself. I considered how he had been deliberately and consciously ready to face death in defense of his country, just as I had been a couple of days prior while crossing the bridge of fire. My feelings of identification and admiration were not shared by my fellow soldiers. In fact, a fellow officer rushed toward the body and took the bayonet off his gun, both as memorabilia and as an attempt to humiliate the enemy. I was unexpectedly overcome with rage and hatred towards this man’s lack of acknowledgement of the bravery of the monkey. I instinctively wanted to protect his body, and at the bare minimum, have our unit spend a few seconds around it to honor the complex relationship that we had with our enemy. I did feel hatred towards the threat he had posed to myself and my soldiers, yet I also was touched by his sacrifice and courage. I was very aware that I could have been the one to be riddled with bullets just a couple of days earlier on the bridge.

In effect, this is what we soldiers are about: walking the tightrope of potential sacrifice while defending our country as heroes. Yet, I suspected that the monkey, like me, had not viewed his defiance of death and willingness to sacrifice as particularly brave or heroic. Rather, his act was a way to embrace life in its fullest. Ironically, saying ‘Yes to life’ meant also saying ‘Yes to death.’

I identified and could understand

the role of the monkey

a soldier who provided his artillery soldiers

with the location of our unit

That he had been willing to die

and willingly sacrificed himself,

without fanfare,

as part of the greater ecosystem of life

and for his country.

This Moment Could be My Last

We survived, at least physically, the crossing of the bridge over the Suez Canal under rain of fire in the 1973 (Yom Kippur) war and the close call with the monkey aiming the artillery on us. Getting closer to our target city of Ismailia, my buddy and I were driving a jeep on a mission in coordination with a sister unit when we lost our bearings and shockingly found ourselves behind enemy lines. There, suddenly and unexpectedly we arrived at a most horrific, eerie sight. In front of us were the widely scattered remains of an Israeli army jeep which had literary evaporated, annihilated into thin air when struck by a lethal Egyptian anti-tank missile. We also stumbled upon the tiny dog-tag, all that was left from an Israeli soldier whose body, like most of the parts of the jeep, had vanished into the same thin air.

Realizing that the jeep we were driving was situated exactly where the evaporated jeep once stood was a surreal experience. We knew that in no time, at any given moment and without warning, we too could vanish and annihilated just like the passengers of the other jeep. We exchanged looks of awe mixed with wonder and horror. As we silently and with full presence inched our way back to our unit, we struggled to metabolize the very real possibility of our instantaneous annihilation and death. Thinking of being evaporated in an instant felt very different than considering dying by a bullet. This really drove home how we had neither control of our destiny nor predictive power as to what might be awaiting us. I truly got it how life, and its continuance, is such a mystery, and ultimately, such a gift.

The scattered remains of an Israeli army jeep

A single dog tag

all that was left of a fellow soldier

In an instant death

could tap her cold, bony fingers

Against our shoulders

And in that unreal moment

Life suddenly became more sacred

When my Calf was Blown Off in Battle of Ismailia: Am I a War Hero or My Parents’ Sacrificial Lamb?

In the waning minutes of the Yom Kippur (1973) war, I once again found myself at the aweinspiring boundary between life and death during the Battle of Ismailia when I was seriously wounded after most of my left calf was blown off and I collapsed in complete and utter silence. The silence, as I put together months later, was partly due to the fact that I lost my hearing when the intense enemy bombing ruptured my eardrums. As soon as I collapsed into this zone of silence and injury, as if someone had literally pulled the rug from underneath me, I told myself, “I lost my leg because I should have not gone (or walked) to a war that I did not fully believe in.” (Later in life I followed up on this interpretation and explore in depth the constructs of the ‘metaphor of illness’ or the meaning of dis-eases.)

I was evacuated under heavy fire, and to my deep distress found myself in an armed vehicle, which I knew to be an easy target for the enemy’s lethal shoulder missiles. What was strange about the morphine-induced delirium I experienced during this evacuation was that I became less worried about being blown up by a lethal Egyptian shoulder missile than I was about being part of an imaginary ‘cosmic play,’ in which I was the sacrificial lamb to my peace-loving parents who were simultaneously and paradoxically against the war while proud of their ‘sacrificial hero/wounded lieutenant son.’ Years later, in an attempt to make sense of this bizarre but intriguing experience, I devoted considerable time to exploration of what is known as the Medea Complex, or the unconscious wishes of parents to kill their children as manifested by the 25 years (one generation) average of war cycles in modern times.

War hero, sacrificial lamb

In a war I did not fully believe in

My left calf, blown apart

Like the peaceful beliefs that had been planted,

like tulips in my heart

The world around me, sounds, colors

Faded in, briefly

My life, my being, my very essence

My fate, left in the balance

Between the desert and the cosmos

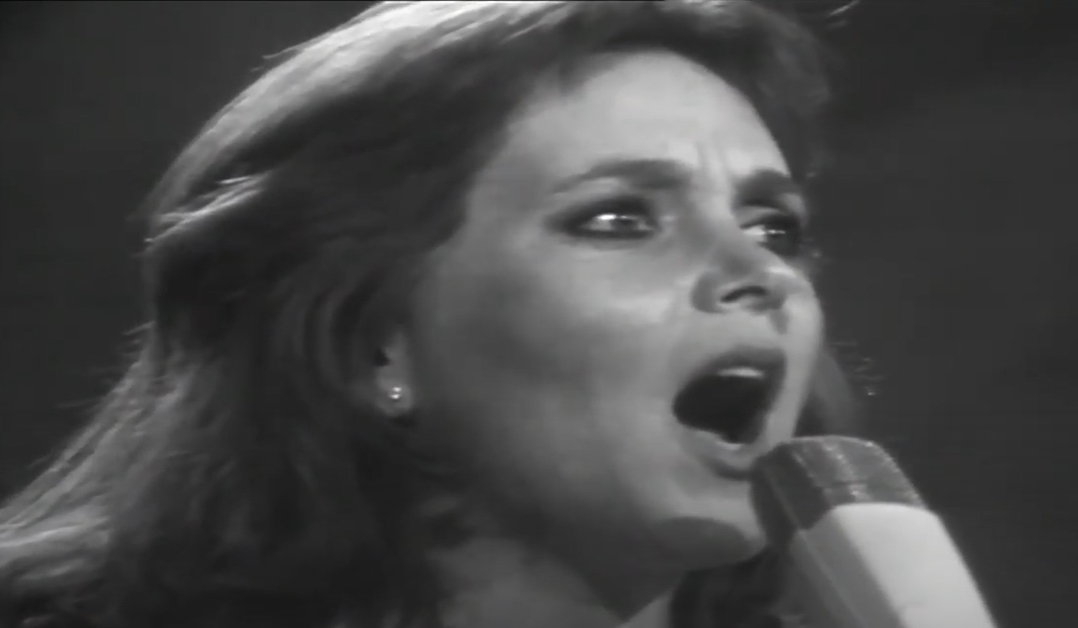

Song for Peace – Shir Lashalom

The powerful protest Song for Peace, a first of its kind in Israel, was sung for the first time in 1968, a year after the “Six Days war” was won, to a nation still drunk on victory. It premiered in my basic training boot camp by Miri Aloni and Lehakat Hanchal להקת הנח”ל [Lyrics: Yankele Rotblit; Melody: Yair Rosenblum; Complete lyrics & translation.

Bold, pacifist, and uncompromising, it touched many of us deeply at the time, and ever since, with its fearless message. It calls for the victorious people, and its army, to let go of the dead, to stop idealizing them, to stop the fighting on their behalf (in an endless cycle of death and wars), to stop whispering a prayer for peace, and instead to actually, yell it out loud and more importantly, bring it on!

50 years later, both the song and its potent message still reverberate in my body whenever I hear it, or sing it along.

Song for Peace

Let the sun rise

the morning give its light

The purest of prayers

will not bring us back

He who’s candle was snuffed out

and was buried in the dust

bitter cry wont wake him up

and wont bring him back

Nobody will bring us back

from a dead and darkened pit

here, neither the victory cheer

nor songs of praise will help

שיר לשלום

תנו לשמש לעלות

לבוקר להאיר,

הזכה שבתפילות

אותנו לא תחזיר.

מי אשר כבה נרו

ובעפר נטמן,

בכי מר לא יעירו

לא יחזירו לכאן.

איש אותנו לא ישיב

מבור תחתית אפל,

כאן לא יועילו

לא שמחת הניצחון

ולא שירי הלל.

The silent prayers for us

Like balloons released towards the heavens

The dead who died fighting will not

return, will not roam the earth again

Will not laugh or cry

If you honor us

Instead of singing songs

Use your voices to shout for peace

To stop endless wars that take your loved

ones to dark graves void of light

I was a boy – Lahakat Hanahal; להקת הנח”ל – הייתי נער

An equally powerful song that has stayed with me since my youth, and is likely to linger for the rest of my life is I was a boy also sang by Lahakat Hanahal. Lyrics: David Atid; Melody: Yair Rosenblum; Translation: DeAnna L’am

Heart-breaking and beautiful, the song captures the lifelong permanent damage suffered by millions of (the best of the best) young men who have been routinely, every generation, recruited to fight wars all over the world in the past 10,000 years. I am among those millions who were indoctrinated to fight to the bitter end, and to sacrifice our lives for the, often, senseless causes of our leaders, parents, as well as variety of economic forces, including the obvious, military industrial complex.

One of my dissertation topics was: “The Medea Complex and the Cycle of war” where I intended to explore the fact that wars, on average, take place globally in 18-22 years cycles, which is, like Medea who killed her children, the older generation sends the younger generation to war where the ‘best die first’ thereby the challenge to the older generation’s authority and power is significantly reduced.

The Rolling Stone powerfully attempted to address the same ‘post (Vietnam) war’ dynamic in their forceful song I want to paint it black.

Generally, ‘we’, young soldiers are barely 18 years old when we go to war to inflict destruction and to readily meet death: of our brothers, of the “other”, and possibly our own. This song potently describes all that we lost in the process: life, energy, power, innocence, trust, the ability to love, and perhaps most importantly the excitement and exuberance of our adolescence.

I was a Boy

The targets are cleansed and destroyed

Snow on mount Hermon melts in the sun

In a ghost town on the Golan Heights

A lonely donkey is lost like before the war

Summer returned to its old strongholds

But your face, my boy, remains changed.

Curtains and window blockers were removed

The city clerk locked the bomb shelters

Grasses climb and grow

Fresh greenery over scabs and canals

Pomegranates returned to market booths

But your face, my boy, remains changed.

I had a boy in love, I had a boy,

Clear was his voice, clear were his eyes

The battle now silent, he returns to the gate

But his gait is heavy, and his face sealed.

הייתי נער

היעדים מטוהרים והרוסים

שלגים על החרמון מול שמש נמסים

ובעיירת רפאים על הרמה

חמור בודד תועה כבטרם מלחמה

הקיץ שב למשלטיו הישנים

אבל פניך נערי נותרו שונים

הוילונות הוסרו והנייר גורד

פקיד העירייה נעל את המקלט

שלוחות הדשא מטפסות ומעלות

ירוק טרי על צלקות התעלות

הרימונים חזרו לשוק לדוכנים

אבל פניך נערי נותרו שונים

היה לי נער מאוהב היה לי נער

צלול היה קולו צלולות היו עיניו

הקרב נדם ושוב קרב הוא אל השער

אך הילוכו כבד וחתומות פניו

Life resumes

Snow melts on Mount Hermon,

cleansed by the golden sun

But the boy’s face has changed

Is covered with worry, twisted, shriveled

a mirror reflecting the horrors of war

The battle has ended in the desert

But has just begun in the boy’s mind

A lifetime of suffering

An innocent, lost

The Crater Dilemma: Instinct vs. rational & impulse vs. logics

Another memory from the 1973 Yom Kippur war: we are deep in the desert and artillery shells, with their lethal downpour, were raining down all around us. Each exploding shell created a crater in the sand. I was standing at the edge of one of these craters, covered with dust from the latest explosion. Obviously, my instinct told me to run for my life, to run as fast as I could away from that crater before the next shell struck, but my military training repeatedly ran through my head telling me that ‘two bombs never fall in the same place.’

Accepting that premise meant that this new crater was the safest place around and therefore I should jump into it, against all my instinct. In the confusion of life and death, it was the fight between intuition and the brain – instinct vs. rationality. I jumped into the crater, which probably saved my life. I have, since that day, always wondered how many times in life we stand at the edge of craters needing to weigh our instinct against our rational inclination; our impulse against the logical choice. Indeed, life presents us with situations where a crater may even sink us into the earth, but where the seeds of creativity may flourish. (Listen to an audio recording, describing this junction)

A recollection of the 1973 Yom Kippur war,

shells exploding,

undisturbed sand became a bed of craters,

for us soldiers to hide in perhaps,

from the storm of shells that poured fire on us

even impulsivity had reason over logic,

meant life and not a sudden death

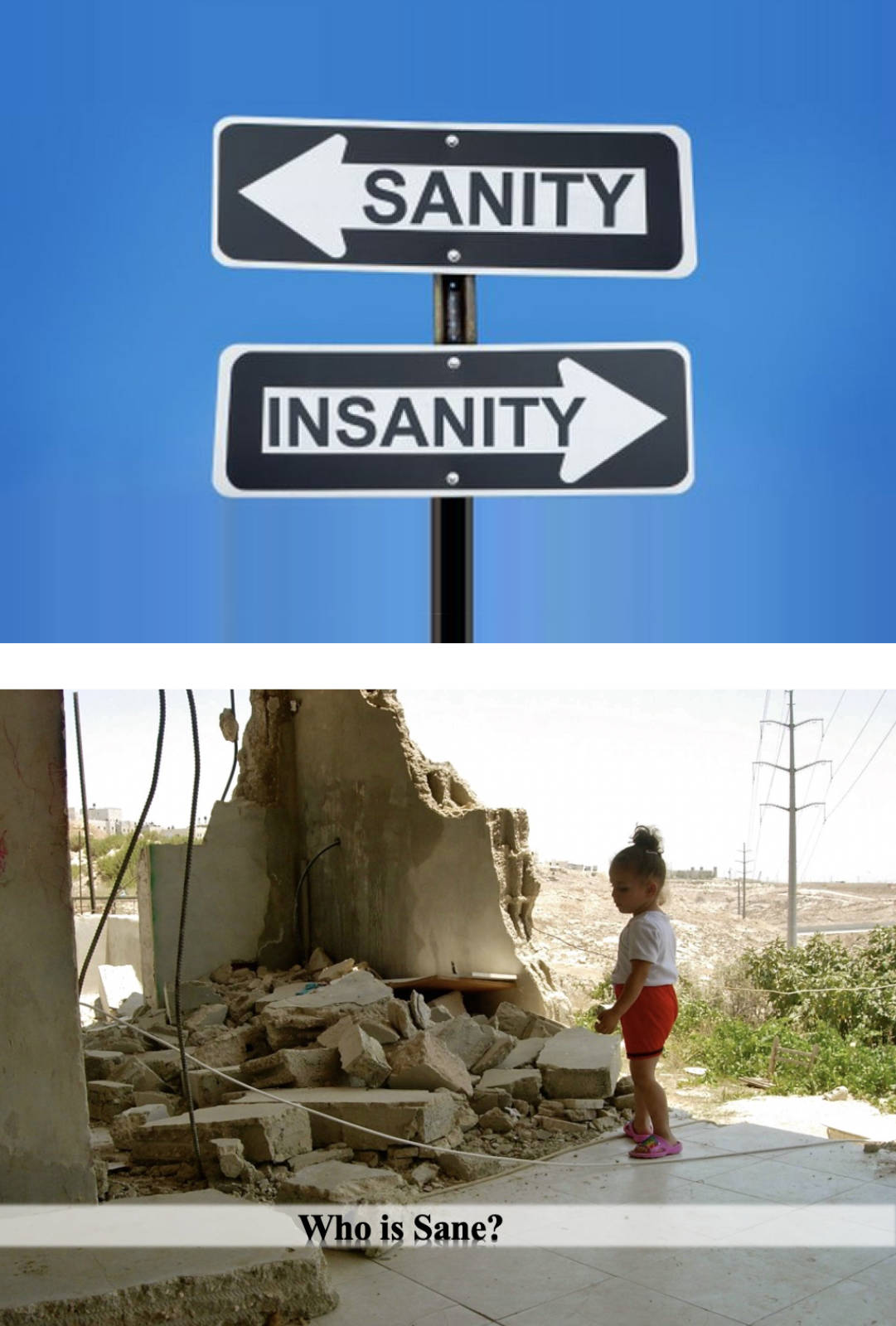

Occupation of West Bank & Gaza: Being Sane in an Insane Place

Thinking back to my early years, I can see that encounters with death during my military service, testing boundaries, questioning commonly held beliefs, seeking the truth, questioning authority, and searching for ways to choose between intuition and logic were all inherent parts of who I was. I loved to learn by examining what I or others thought was right or wrong. I did not do it alone; for example, there was an incident where some soldiers did not come back from an R&R furlough to the base in the Gaza Strip, but instead admitted themselves to a mental institution [to avoid returning to the base in Gaza]. This meant that I could not give a much needed break to other soldiers in our unit and I was furious. I expressed my outrage to my mother on the phone. In a soft voice, my mother responded to my anger by saying, “Perhaps those who admitted themselves to the mental institution rather than coming back to the camp were the sane ones”. I was speechless. In that one, short sentence, she forced me to question the whole notion and definition of sanity. In my own way, I continue this path.

Outraged at the offense of others

Who hid, feigning insanity

Angry at them for their callousness

And lack of service

They refused to fight

their defiance saved themselves

from the real insanity of war

Rehab.: Kicking my Surgeon’s Butt with My Calf-Less Leg

As part of my rehabilitation from the 1973 war injury, I remember the oddest scene in the hospital where I rudely and highly inappropriately confronted my young surgeon in the hallway in front of other wounded soldiers telling him something to the effect that, “You told my parents that you hope I will be able to walk well one day. It won’t be long before I walk normally and kick you with my calfless leg.” Without hesitation, the doctor slightly rattled one of my crutches, which caused me to lose my balance and fall to the floor, humiliated, in front of my fellow hospitalized soldiers. The doctor then said to me something like, “If you can walk so well, why don’t you walk without crutches right now.” Oddly enough, this proved to be a ‘magical and highly effective dose of medicine,’ and at that very moment, I knew I would fully recover, which indeed I did. Within a year of my injury I played college ball on the basketball team of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and years later I make a career of deep see diver, climbed Kilimanjaro, played competitive Ball to age 55yo, drove motorcycles in the Himalayas and much much more.

My dose of medicine

A rattling of crutches done by my surgeon

An elixir, the motivation I needed

To walk, to heal from a devastating injury

To push my body past the limits of what I thought possible

Idiotic Myth: “Israeli Paratroopers Don’t Get PTSD”

Right after this bizarre scene with my doctor, I started training myself to walk again. I rejected any physical therapy and spent long nights, all alone, walking on the hospital room porch, holding on to the rail, and ‘silently’ crying in pain. When I eventually went back to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem to continue my studies, I also went back to riding my motorcycle and playing basketball on the university team. The subsequent surgeon, unusually but effectively, used my performance on the basketball court as a yardstick to measure when I was ready for the next surgery. Obviously, this injury was followed by a few years of intense pain, determination, surgeries, rehab, deep contemplation, and finally, full recovery in spite of a very poor prognosis. It took me many years to attend to the traumatic aspect of the war injury & war experience and numerous other traumas I’d experienced in my lifetime and embrace the illuminating concept of Post Traumatic Growth (PTG) rather than Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

Learning to walk again

alone At night

the only sound, My heartbeat

feeling intense waves of pain

Looking for an oasis of healing

A spring inside of myself

A determination to heal, spiritually,

Physically and emotionally.

Becoming an Oceanographer: Save the World from Starvation

I received my B.Sc. in Physical Chemistry from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in June 1975, heading in the direction of studying oceanography, which, for me, was an ideal combination of science (chemistry), adventure (deep-sea & free diving), and idealism (saving the world from starvation). I was intrigued with the idea of growing unlimited amounts of protein (fish) in the oceans, which, after all, cover more than 75% of our planet. Working for the Marin Laboratory in Eilat, I built this raft and conducted the research on floating fish cages and feeders in Dahab, a precious and glorious dot on the map on the pristine Red-Sea shore of the Sinai Peninsula.

Save the world from starvation

Had been my aim,

to help people grow unlimited amounts of protein through fish

My adventurous spirit soared in the ocean

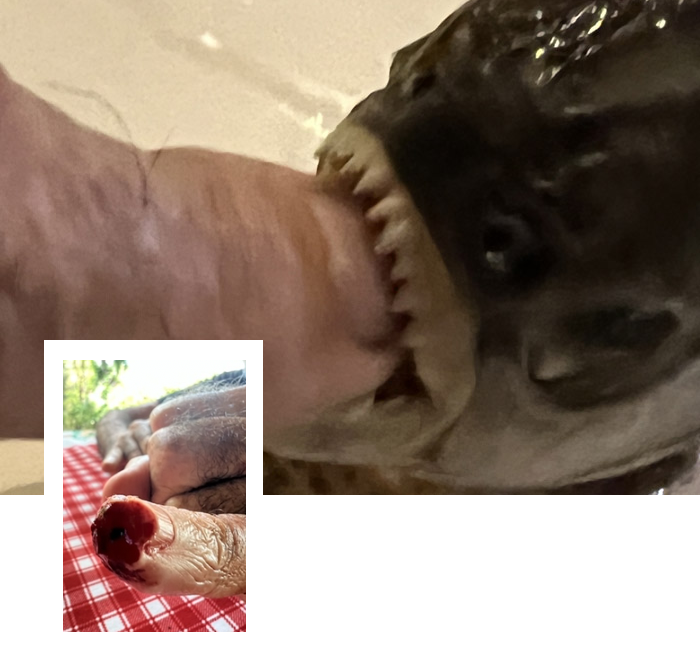

Diving the ‘Diver Cemetery’ – The ‘Blue Hole’ 184ft (!) at Dahab

As part of me being an oceanographer, I was also a deep-sea diver where I regularly dove the spectacular coral reef in the warm and clear waters (up to 300 feet visibility) amid brilliantly colored fish, turtles and eels. I also dove with sharks in Ras Muhammad off the tip of Sinai next to beautiful and rarely visited or touched coral reef. But most thrilling and risky was adventure-diving (with the standard of air mixture of 21% oxygen, 78% nitrogen) the Blue Hole, also known as “The World’s Most Dangerous Dive Site” with the nickname “Diver’s Cemetery” with a depth of over 200 feet (60 meter)! It is estimated that it claimed the lives of 130 to 200 divers in recent years, primarily due to Nitrogen Narcosis.

Diving with sharks in Ras Muhammad

off the tip of Sinai

next to beautiful and rarely visited or touched coral reefs,

an exhilarating blend of risk

And reward

Pleasure and pain

Life, and the very real possibility of death

Motorcycle & the Sense of Boundless Freedom & Exhilaration

As I move through this map of my life, motorcycles appear again and again. I was introduced to motorcycles by my father and found riding them not only fun and exciting, but also a cross-generational continuity with my father. I have carried on this tradition with my sons and nephew whom I introduced to the love of riding bikes – a passion we all still share. Back then, in the Sinai, I rode my motorcycle (BMW 1954) which, as always, gave me a sense of boundless freedom and exhilaration.

My life, navigated through hills and valleys riding motorcycles,

a link between the present and past

My father passing his love of motorcycles on to me

And likewise my admiration for the vehicles

a gift from the heart given to my sons.

Sailing at Dahab and the feelings of Unboundedness

Sailing in my one-person sailboat on the Red Sea, negotiating the water and wind while gliding on the surface of the sea was another multiple boundary experience. Towing my small sailboat behind my heavy motorcycle, carrying my diving gear on the back of my bike, and parking on the reef, was a superb way to reach remote and exquisite diving and sailing places.

Unboundednes

Other worldliness

Gliding in a sailboat

Braving the waters, the wind blowing at my back

Exploring the Red Sea

Fearlessly

“All of you guys are missing some parts!”

Two young ones, not quite adults, still nourished by the springtime of possibilities. We held hands and while walking the coast-line of the Red-Sea, immersed in the calm beauty of the sunset, enjoyed the silence of getting to know each other. She was a 19 year old young Israeli woman. I was a few years older and we had just met. We touched each other softly with a sense of innocence and wonder, more exploratory and curious than sexual. We sat with legs crossed, her head on my shoulder, as we watched the slow decent of the sun. Her soft fingertip touch came to the place where my calf was blown off in the war. She briefly paused and broke the silence by casually offering up: “All of you guys are missing some parts, aren’t you?” Then, she continued to silently and gently stroke my leg. She said it as a simple matter of fact. She could equally have said “The ocean temperature is moderate.” It was a powerful, insightful and profoundly sad moment for me. While, like most of my fellow soldiers, I was still in denial of the profound traumatic impact of my battle experience and war injury on me, it was painfully clear to me that this young woman was already completely resigned and profoundly aware of the, so called “parts” that so many of us, young men – soldiers, “were missing”.

“Missing some parts”

Parts suddenly removed

Limbs blown off

Our souls not quite intact,

Grappling with a broken body

From the injuries of yet, another war

The “Betraying son”

Working as an oceanographer in Dahab, I was extremely lucky to be mentored and kind of ‘adopted’ by my boss, a kind and brilliant scientist. He taught me the basics of marine biology, we went on exciting diving and sailing excursions in the Red Sea, and were close friends. About two years into the relationship, standing on my research raft in the middle of the bay, I was excited to tell him that I was heading to East Africa to apply what he had taught me, to do research on fish ponds. I expected him to be proud of me and was utterly shocked when he exploded in rage and actually came at me jabbing his fists. I learned a few years later that it was similar to what happened when Freud turned on Jung, as Jung announced that he was going to pursue his very own new track of Jungian psychology. Almost exactly the same way Freud exploded on Jung, my friend and mentor called me the “betraying son”, erupting with accusations of how ungrateful I was and how I would not amount to anything without him. To punctuate this archetypal scene, we got into an actual (rather spectacular) fist-fight on the research raft on the beautiful clear water of the Red Sea. Learning from this experience, I have taught numerous supervisors and mentors over my long career about the difficult challenge for mentors-supervisors to ultimately graciously accept their supervisee as equals who have their own path and who, at times, may even surpass them.

The scene, bizarre, my mentor,

a brilliant scientist,

someone whom I loved and admired

Admonishing me for excelling in marine biology,

and applying what he had taught me

through research on fish in the ocean

My heart, like a crumpled piece of paper

That was no longer wanted,

discarded was our friendship

As we fought on a research raft on the Red Sea

Part 2: War - Oceanography - Diving

Part 3: Adventures in Africa - Europe

Part 4: Psychology of War - Psych of Victim - Family

Part 5: Contributing to the Field of Psychology - Travel/Adventure

Part 6: More Family - Travel/Adventure - End of Life - Teaching

Part 7: Writing - Family - More Adventures - More 'Doing Good' to 70 y.o.

Part 8: Next (Final?) Stage in life 70+ y.o.

Sample of the

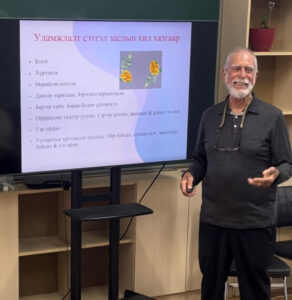

Sample of the  I was super excited that I was invited to present in person and via zoom on May 11, 2024 in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia (with simultaneous translation into Mongolian), for Mongolian psychologists, educators, social workers, and legal professionals on

I was super excited that I was invited to present in person and via zoom on May 11, 2024 in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia (with simultaneous translation into Mongolian), for Mongolian psychologists, educators, social workers, and legal professionals on  In a once of a life-time experience I was also invited to be a co-therapist for a highly educated Mongolian client, who spoke English well and requested me to join her therapy after a short exchange in the waiting room.

In a once of a life-time experience I was also invited to be a co-therapist for a highly educated Mongolian client, who spoke English well and requested me to join her therapy after a short exchange in the waiting room.

The last part of the trip I fulfilled another dream of mine and went (with Tal) to the famous, unique and “ultimate boundary” Demilitarized Zone (

The last part of the trip I fulfilled another dream of mine and went (with Tal) to the famous, unique and “ultimate boundary” Demilitarized Zone (